The Nosema Problem: Part 7a – The Causes of Dysentery in Honey Bees — Part 1

Contents

Why would a colony exhibit signs of dysentery?. 3

Microbial dysbiosis or parastism.. 5

The link between pollen and nosema. 7

How about those “winter bees”?. 8

The Nosema Problem: Part 7a

The Causes of Dysentery in Honey Bees Part 1

First published in ABJ December 2019

Randy Oliver

ScientificBeekeeping.com

Okay, I’ve called into question whether nosema of either species actually causes dysentery. But since dysentery in the hive can clearly spread nosema spores, we should do our best to help our bees to avoid it. To do so, we should understand what factors do contribute to dysentery.

The terms “diarrhea” and “dysentery” are often used interchangeably, but as best I can tell, diarrhea is the name for the symptom of producing frequent, loose stools, whereas dysentery indicates an infection of the intestinal tract. For the purposes of this article, I’ll use the term “dysentery” as it is commonly applied to beekeeping ― the field sign of voided feces dripping down the hive near an exit point (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Given a chance to fly during a warm spell in winter, some of the exiting bees appear to be so eager to relieve themselves that they do so the moment they take flight. But does this mean that they are diseased?

The photo above suggests the importance of flight opportunities during the winter. Should those ready-to-burst bees have instead let loose inside the hive, they might have spread nosema spores. Luckily, nosema-infected bees are prone towards flying out of the hive even when it’s cold, perhaps due to an ingrained behavior that helps the colony to remove infected individuals [[1]]. Note the number of dead bees in the snow. Since nosema hampers energy production in a bee, infected individuals may not be able to return to the hive, thus helping to prevent them from infecting their sisters.

So nosema may induce suicidal winter flight by infected workers, but that doesn’t mean that it caused dysentery. I’m open to the possibility that it could, but my current overall assessment is that we should refrain from repeating the apparently unsubstantiated claim that nosema causes dysentery until Koch’s Postulates have been fulfilled by peer-reviewed research — meaning that someone needs to demonstrate that infection by nosema actually does induce bees to exhibit dysentery.

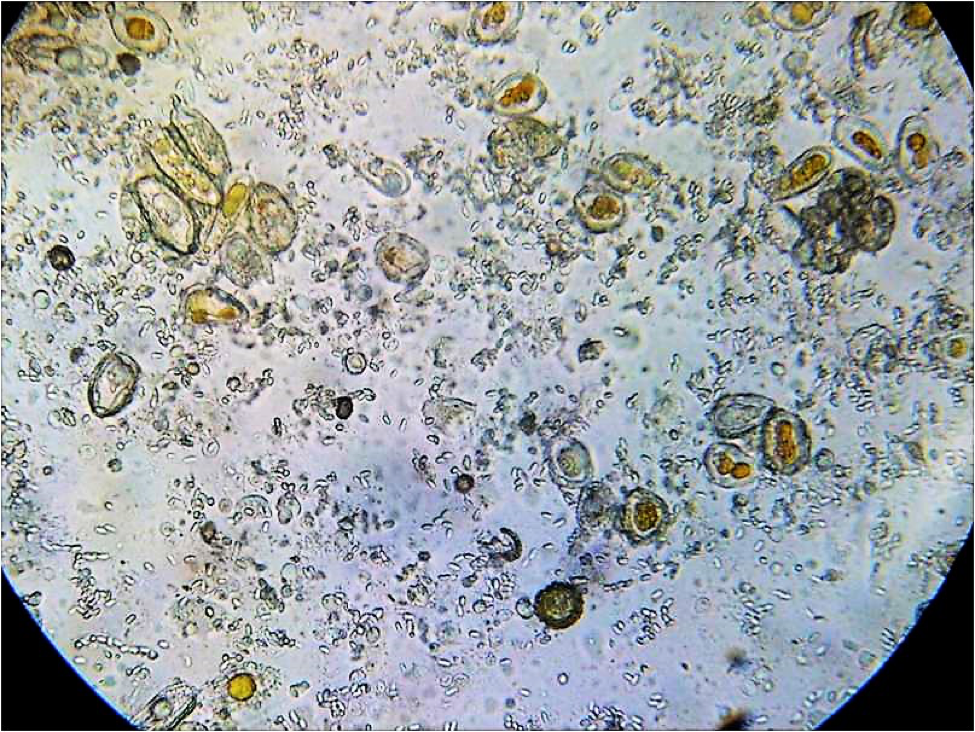

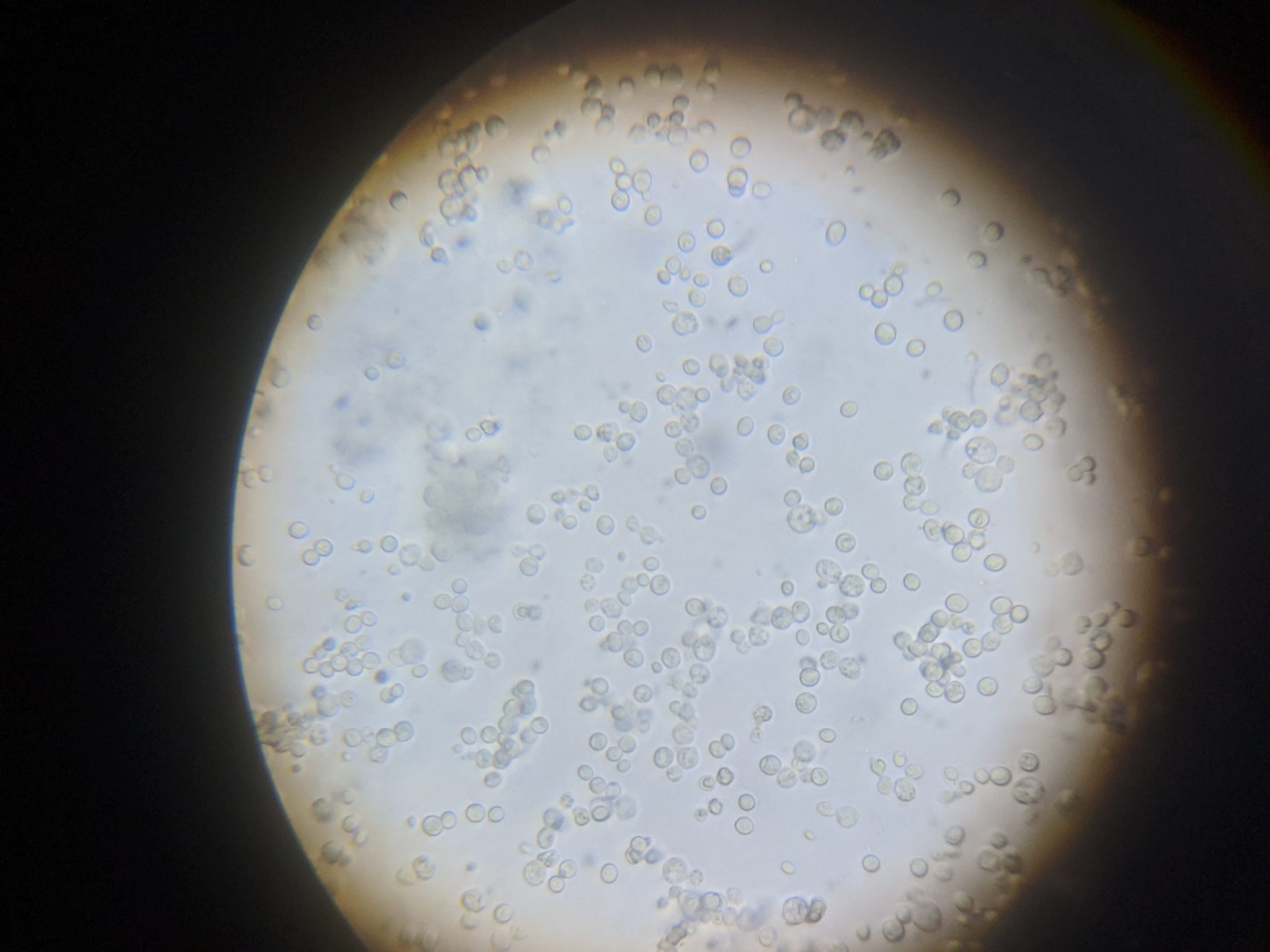

That said, I’ve looked at a fair amount of dysentery scrapings under the ‘scope — there are sometimes nosema spores present, but as far as I can tell, no more often than in bee samples taken from nearby hives not exhibiting dysentery. But I do often see other indications of gut dysbiosis (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. I’m no microbiologist, but I often see abnormal things in bee guts. Here’s a field of view of diluted gut contents (at 400x) full of nosema spores (the very small pill-shaped objects), and what may be some pollen grains (the dark objects). But there are also what appear to be rust fungus spores (orange centers), and perhaps some yeast cells, amoeba, or other organisms (the grayish oblong, round, or irregular objects).

Practical application: Seeing signs of dysentery is likely never a good thing, but keep in mind that it could be caused by any number of things. If you’re worried about nosema, get a microscope and confirm that the pathogen is indeed prevalent in the hive(s).

Why would a colony exhibit signs of dysentery?

By nature, honey bees are fastidiously clean within the hive. This is extremely important for a colony of eusocial insects, what with so many bodies packed into a small cavity for long periods of time. Therefore, there has been strong evolutionary pressure for bees to avoid defecating within the hive. Thus even young nurse bees take short “cleansing flights” to relieve themselves — but generally not on the hive itself. In general, it’s only when the bees have been constrained by weather from flying out to void (or when a colony is really sick), that you see the telltale signs.

Experts have blamed dysentery on any number of factors. Allow me to quote Dr. White in 1919 [[2]]:

When discussing nosema and dysentery, one thing to keep clear is that the nosema parasite reproduces and grows in the bee midgut (ventriculus) — only its inert spores show up in the hindgut (rectum). Dysentery (diarrhea), on the other hand, is a sign of a disorder of the hindgut, apparently due to chemical irritation, microbial dysbiosis, a poorly-digested diet, a sudden switch to a pollen that is irritating, or to which the bee gut microbiota were not adapted, consumption of a honeydew containing complex sugars, minerals, or other phytochemicals, or an infection by yeast or Malpighamoeba mellificae.

Wow, that’s quite a list! Nowadays you can add poorly-digested pollen subs, contaminated or fermented sugar syrup (containing yeasts or other fungi, molasses, flavorings, or floor sweepings), or some of the homebrew potions that beekeepers feed their colonies. Unfortunately, most authors that list causes of dysentery fail to provide citations of supportive evidence to back those claims, so let’s go over what I could find …

honeydew

In 1914, E.F.Phillips [[3]], when measuring temperatures in overwintering colonies, observed that:

Honeydew honey is a poor food for winter and is so recognized. It contains the same sugars as honey, but contains in addition a considerable amount of dextrin [as well as other indigestible complex sugars and perhaps a high mineral content]… From the evidence at hand it appears that dextrin cannot be digested by bees and, whether or not this is the explanation, honeydew honey causes a rapid accumulation of feces which usually results in the condition known as dysentery, in bad cases of which the feces are voided in the hive. In the case of [a colony wintered on honeydew] the whole hive inside and out, as well as the frames and combs, were spotted badly, the inside of the hive being practically covered. Even with fine honey stores such a spotting is usually noticed after a prolonged confinement, especially in severe weather (or during brood rearing). It therefore appears that the accumulation of feces acts as an irritant, causing the bees to become more active and consequently to maintain a higher temperature. We are therefore justified in believing that the cause of poor wintering on honeydew honey is due to excessive activity, resulting in the bees wearing themselves out and ultimately in the death of the colony…

It therefore follows that excessive activity causes the consumption of more food, resulting in turn in more feces, so that colonies on poor stores are traveling in a vicious circle, which, if the feces can not be discharged, results in the death of the colony. In the work here recorded no attention was paid to the theory that dysentery is due to an infection, since there is nothing in the observations made that lends any support to that idea.

On the other hand, more recently Pohorecka and Skubida in Poland studied the relationship between wintering on honeydew and colony health [[4]], tracking a total of 1400 hives over the course of three winters.

In this study… no increase in mortality rate among bees related to the percentage of honeydew honey in winter stores was found. It shows that wintering performance is significantly influenced by other factors such as duration of the wintering period, colony strength, and the positioning of honeydew honey containing stores in the nest as well as the extent to which the stores are used up.

Unfortunately, they did not record whether dysentery was observed. However, their data suggested that the presence of honeydew in the bees’ diet actually decreased infection by Nosema apis.

Practical application: Some honeydews or other irritating foods may cause dysentery.

Microbial dysbiosis or parastism

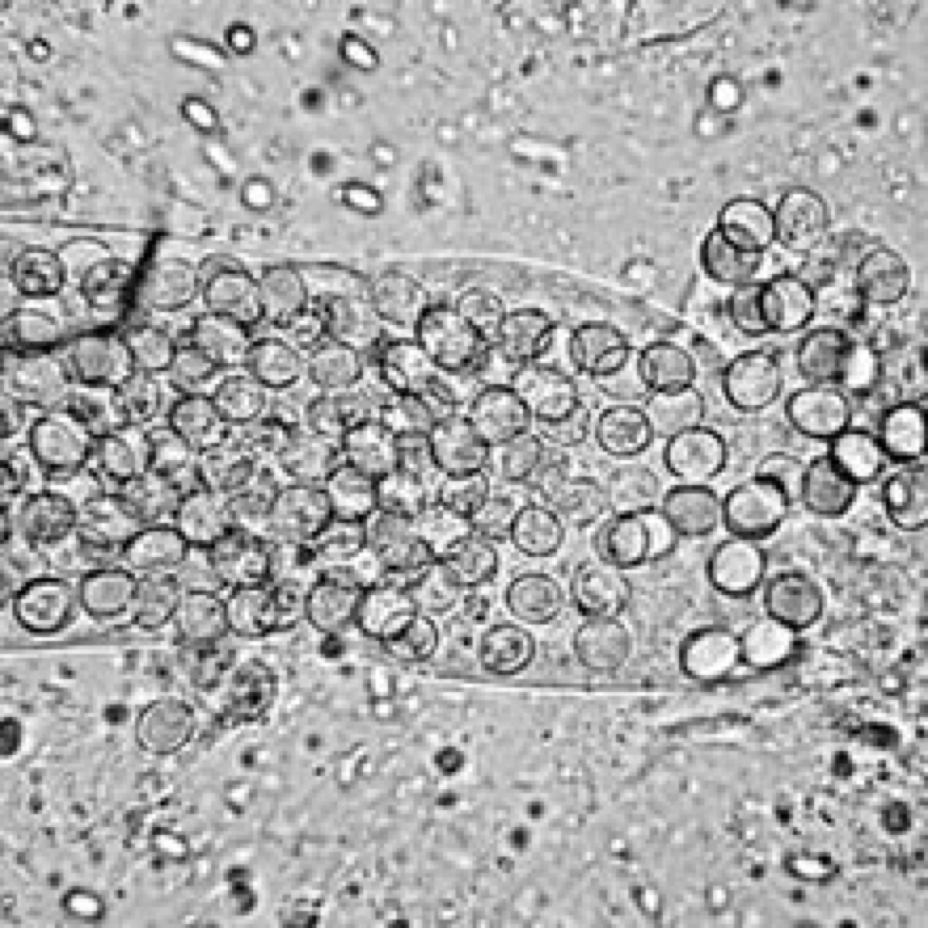

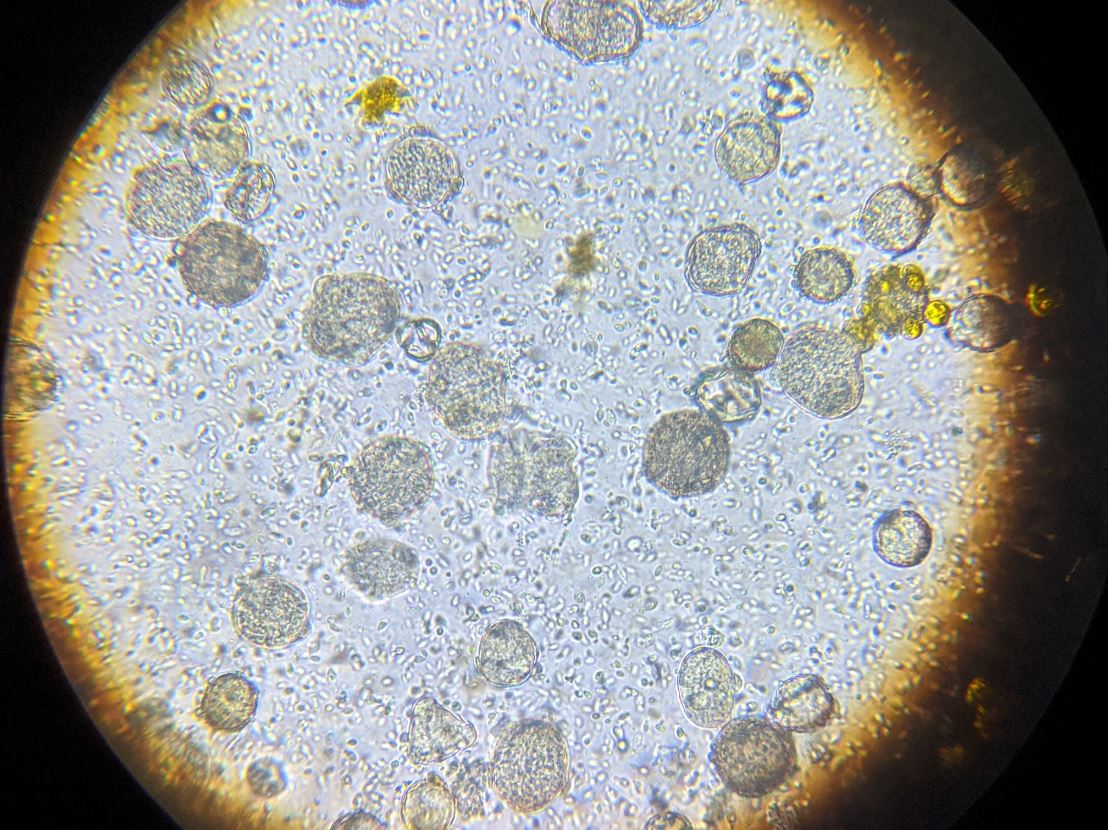

Something that I sometimes observe in dysentery samples are round objects that appear to be amoeba cysts (Fig. 3). Prell [[5]] cited Dr. Morganthaler of Switzerland, who described that with amoeba infection “there is often a soiling of the alighting board, and even of the inside of the hive, by faeces containing cysts.”

Figure 3. The round shapes in this image from Wikipedia [[6]] are identified as Malpighamoeba mellificae cysts. Note also the presence of the glowing nosema spores

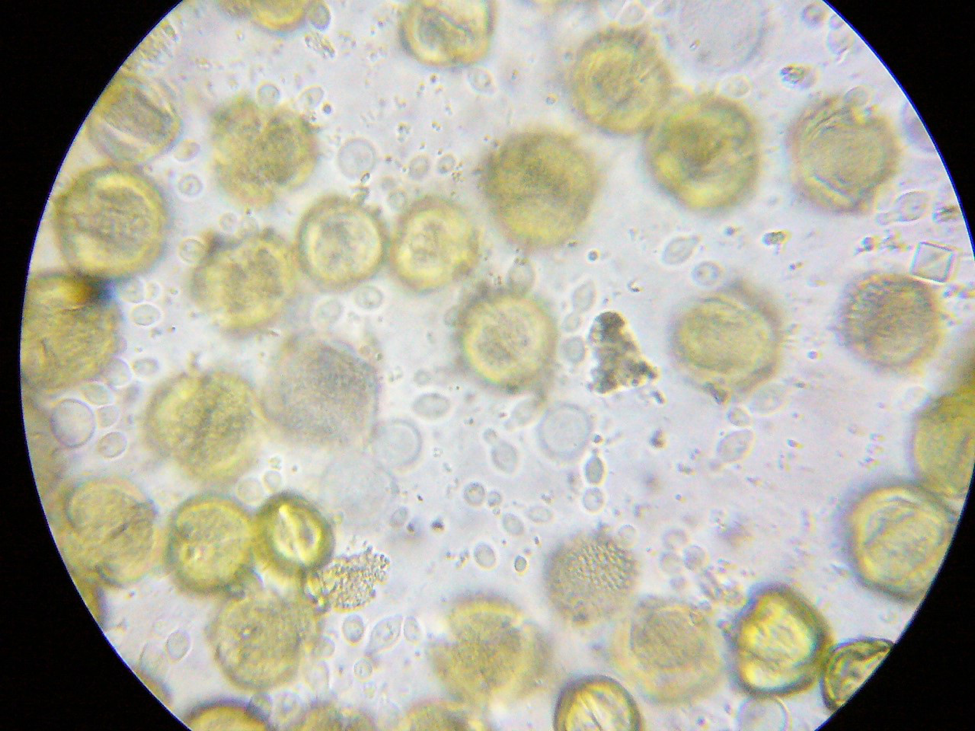

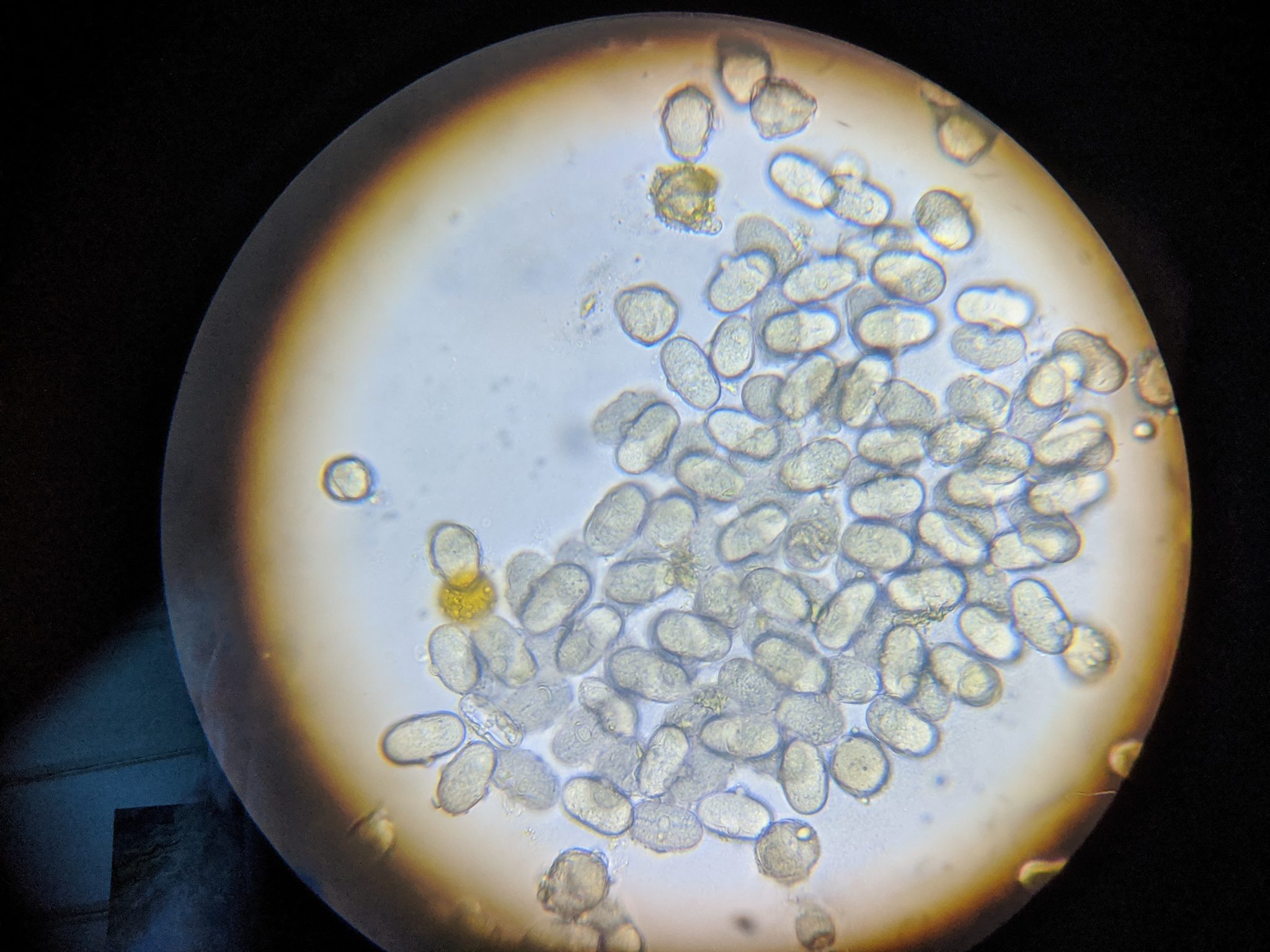

And then there are yeasts (Fig. 4), whose presence in the bee gut indicates that some form of dysbiosis is occurring, perhaps due to the presence of undigested sugars or excessive water in the hindgut. I’ve observed dysentery to be associated with the feeding of fermenting syrup.

Figure 4. Here is beebread that I mixed with dilute syrup and allowed yeast fermentation to start. You can see what appear to be large grayish yeast cells (I have no idea what the little square object is), and I’m far from certain as far as my identification of the gray cells as yeast.

Update: Beekeeper Georges Prigent questioned me on the identification of yeasts. So I grew some more cultures. Thanks to readers such as Georges for feedback!

Above is bread yeast grown in diluted honey. 400x

Above is bread yeast grown in diluted honey. 400x

Above is a pollen/sugar culture at 400x, which I first suspected the gray ovals to be some sort of organism, but which Georges pointed out were actually pollen grains (which I later confirmed). These grains could be from vetch (Viscia).

Above is a pollen/sugar culture at 400x, which I first suspected the gray ovals to be some sort of organism, but which Georges pointed out were actually pollen grains (which I later confirmed). These grains could be from vetch (Viscia).

Here I grew bread yeast in a mixture of pollen grains and sugar water in order to show their relative sizes. The small ovals that look like nosema spores are the bread yeast. Unfortunately for us microscope-viewing beekeepers, the yeast cells are about the size and shape of nosema spores.

Here I grew bread yeast in a mixture of pollen grains and sugar water in order to show their relative sizes. The small ovals that look like nosema spores are the bread yeast. Unfortunately for us microscope-viewing beekeepers, the yeast cells are about the size and shape of nosema spores.

Dang, now I was curious. So I crushed some nosema-laden bees to make a spore-rich slurry, and put a tiny drop on a slide. Then I put a tiny drop of yeast culture immediately to the left of it, and pressed on a cover slip. I’ll tell you right now, the untrained eye could easily mistake yeast cells for nosema spores! See below:

In this photo, yeast culture is to the left; the nosema suspension to the right. I’ve labeled the numerous yeast cells, and a group of nosema spores to the right.

In this photo, yeast culture is to the left; the nosema suspension to the right. I’ve labeled the numerous yeast cells, and a group of nosema spores to the right.

Tips:

- The nosema spores sink, so they come into focus below the level of the yeast cells.

- The outlines of the yeast cells aren’t as sharp as those of the nosema spores, and the centers of the nosema spores glow a little more brightly.

- But the key difference is that the nosema spores are more regularly shaped than the yeast cells — smoother, more uniform, and consistently sized and shaped.

I now wonder how often yeast infection is misdiagnosed as nosema???

The literature on the impact of yeasts, and their interactions with other microsymbionts is confusing, with some findings suggesting that nosema may either promote or restrict yeast replication [[7]]. Others report seeing sperm-like trypanosomes in bee guts, such as Crithidia, but I’ve yet to notice them, so don’t have a photo to share.

Practical application: The hindgut contents of a healthy bee generally contain only pollen grains in some stage of digestion and pieces of degrading peritrophic membrane. But in dying bees, or those from sick colonies, I often observe all kinds of other organisms or unidentified objects. I do not know whether they induce dysentery, or whether the excess moisture in distended bee hindguts simply allows them to proliferate.

The link between pollen and nosema

There are several ways in which pollen and nosema are linked:

- Pollen brought back by foragers is often contaminated with nosema spores.

- Nosema appears to reproduce best in a bee’s midgut if that bee is consuming pollen.

- A bee’s rectum can quickly fill with the indigestible exines of consumed pollen.

- There is often a lot of pollen available in early spring and fall ― exactly when bees may be confined by cold or wet weather, and thus unable to take cleansing flights.

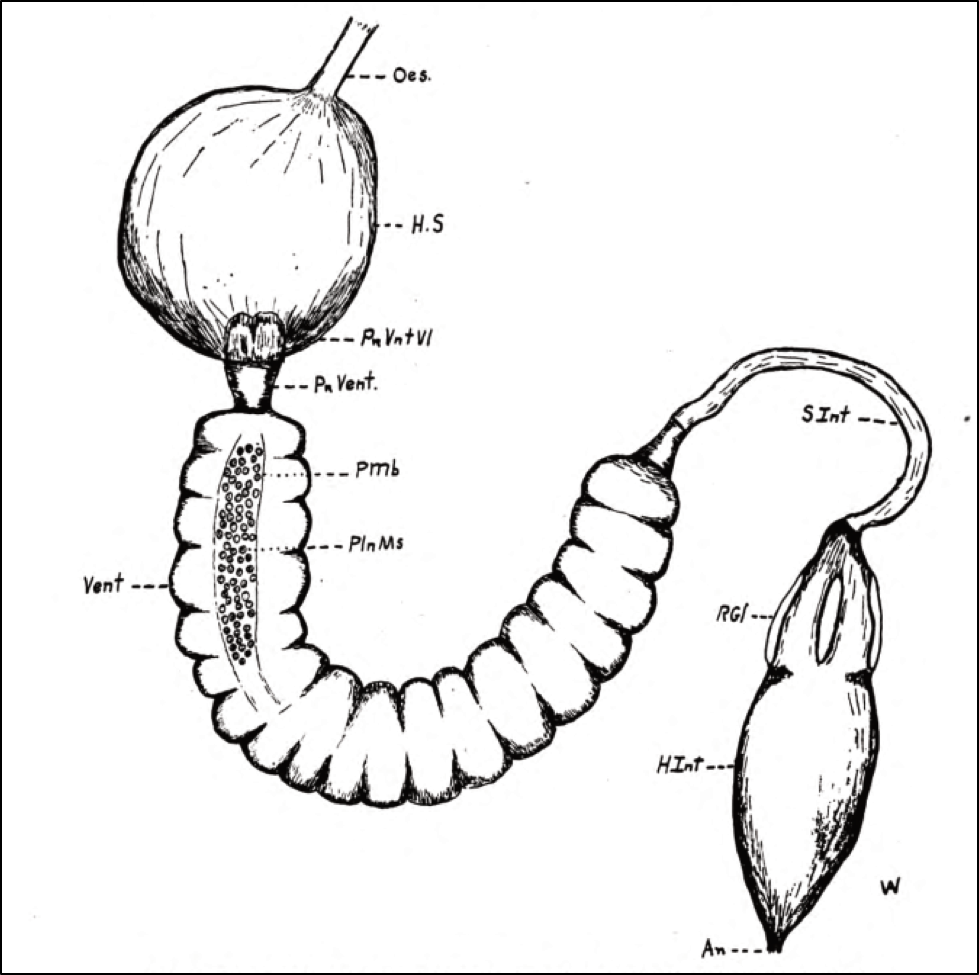

So it’s easy to understand why nosema is typically an issue only in autumn or springtime. So why does it sometimes become prevalent during winter? Could it be due to the consumption of pollen? A deep and detailed study by Whitcomb & Wilson [[8]] on the digestion of pollen by the honey bee did not find any association between the feeding of pollen and dysentery (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Whitcomb made detailed drawings of the process of pollen digestion by the bee, by staining pollen grains mixed in sugar syrup bright red, and the syrup itself blue. Here he illustrated a bolus of ingested pollen grains (enclosed by the peritrophic membrane (PMb) shortly after entering the midgut (ventriculus) from the crop (HS for “honey sac”) It only takes a few hours for the process of digestion to take place, culminating in the largely-emptied exines of the pollen grains being deposited into the hindgut (HInt), where they remain until defecation.

How about those “winter bees?”

Adult bees, if not rearing brood, need very little protein in their diet. Thus, bees can live a long time on a diet of easily-digestible honey alone, and have little need to defecate (such as during winter, or in incubator trials when they are fed sugar syrup alone). By now most of us understand that the long-lived “winter bees” store enough protein and lipids in their fat bodies to survive until spring. So why would winter bees have pollen in their guts?

Some years ago I used fluorescent tracers to track consumption of pollen sub by the bees by freezing samples of bees from the combs, and then crushing them en masse on a grid of 50 crosslines. Normally, only a portion of the bees (the nurses) would contain pollen. But to my surprise, when out of curiosity I crushed a sample of bees in November, every single bee had a gut chock full of pollen (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Why would every bee in the hive in November (as broodrearing ceased) have a gut full of pollen?

Come winter, it appears that the long-lived “winter bees” not only load up their fat bodies, but also fill their guts with pollen. It’s not yet clear whether this phenomenon is simply to store as much protein as possible, or whether it has to do with the pollen exines functioning as a water reservoir in the rectum [[9]]. In any case, this may be why we sometimes see a spike in nosema in fall. But more importantly, could those guts full of pollen later be a cause of dysentery during winter?

Dang, I was just getting on a roll! But I’m out of space. In my next installment I’ll cover what appears to be the main cause of dysentery in bees, and what the bees may do to deal with it.

Literature cited

[1] Węgrzynowicz, P, et al (2014) Causes and scale of winter flights in honey bee (Apis mellifera carnica) colonies. J. Apic. Sci. 58(1): 135-143. DOI: 10.2478/jas-2014-0014

Wolf S, et al. (2014) So near and yet so far: harmonic radar reveals reduced homing ability of nosema infected honeybees. PLoS ONE 9(8): e103989.

Dosselli, R, et al (2016) Flight behaviour of honey bee (Apis mellifera) workers is altered by initial infections of the fungal parasite Nosema apis. Scientific Reports 6:36649 DOI: 10.1038/srep36649

[2] White, GF (1919) Nosema disease. U.S. Dept Agric Bulletin 780, 59 pp. Available in Google Books.

[3] Phillips, EF & GS Demuth (1914) The temperature of the honeybee cluster In winter, Bull. 93, U.S. Dept. Agr.

[4] Pohorecka, K & P Skubida (2004). Healthfulness of honeybee colonies (Apis mellifera L.) wintering on the stores with addition of honeydew honey. Bull Vet Inst Pulawy 48: 409-413.

[5] Prell, H, et al (1926) The Bee Laboratory. Bee World, 8(1): 10-14.

[6] Image open access, from Institut für Saat- und Pflanzgut, Pflanzenschutzdienst und Bienen, Abteilung Bienenkunde und Bienenschutz.

[7] Ptaszyńska, A, et al (2016) Nosema ceranae infection promotes proliferation of yeasts in honey bee intestines. PLoS ONE 11(10): e0164477. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164477

Tauber, J, et al (2019) Effects of a resident yeast from the honeybee gut on immunity, microbiota, and nosema disease. Insects 10: 296.

[8] Whitcomb, W & H Wilson (1929) Mechanics of digestion of pollen by the adult honey bee and the relation of undigested parts to dysentery of bees (Vol. 92). Agricultural Experiment Station of the University of Wisconsin. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89098844962&view=1up&seq=5

There’s also an excellent review of pollen digestion by Clarence Collison at https://www.beeculture.com/a-closer-look-7/

[9] Dr. Kirk Anderson, pers comm.