The Pesticide Situation: Part 2

The Pesticide Situation: Part 2

Randy Oliver

ScientificBeekeeping.com

First Published in ABJ, February 2019

The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act requires that a pesticide will generally not cause any unreasonable risk to man or the environment — taking into account the economic, social, and environmental costs and benefits of the use of that pesticide. The two italicized caveats are what allow each stakeholder to have a different perspective on pesticide use.

The Pesticide Situation is a contentious topic among beekeepers. There are those who divide everyone else into either of two groups — those who agree with them, or those who are complete morons. I, on the other hand, have found that I learn little in an echo chamber. Indeed, in order to truly understand an issue, one should be able to argue either side’s perspective with equal facility. Thus, I go out of my way to understand the viewpoint of the “other side”.

But rather than simply accepting others’ opinions, I then check out the supporting evidence and scientific interpretation. To that end, in trying to understand The Pesticide Situation, I not only read widely, but also talk to growers, beekeepers, and ecotoxicologists. I thank the many beekeepers who’ve endured my grillings about their pesticide issues, and especially appreciate my conversations with those who are both commercial beekeepers and farmers–who thus see the issue from both sides. The end result is that when I was asked to write an article on pesticides and bees, I soon realized that I couldn’t begin to objectively cover the subject in a single installment—thus you’re reading what’s turned into a series.

So let’s continue by seeing whether I can fairly represent the viewpoints of the various stakeholders—I’m happy to receive emails for suggestions as to things that I may have missed.

The stakeholders

The majority of my readers will be beekeepers; and we of course have a pretty one-sided view about pesticides. But we beekeepers constitute less than a tenth of a percent of the population, and until recent years were generally regarded as weirdos who for some reason kept stinging insects in boxes.

But everything changed when colonies suddenly, and inexplicably, started dying in the early 2000’s. The key word was “inexplicably”, since this caught the media’s (and thus the public’s) attention.

Practical application: although those colony losses were painful to us, it was our good fortune that the sting-ey honey bee was suddenly turned into a beloved poster child for a public coming to terms with the fact that human actions appeared to be possibly threatening that now cute and fuzzy little critter with imminent extinction. Keep in mind that if it weren’t for the demands of the almond industry in California for this non-native invasive insect, our plight might have remained invisible.

The media loved “the sky is falling” story — and it was even better that the death of our bees was apparently due to some mysterious unknown culprit (Fig. 1). Pesticides and the evil chemical companies were obvious suspects, just begging for a lynching.

Figure 1. Fear sells. In preparation for the above issue, the Science Editor of Time phoned and interviewed me for an hour. I carefully explained the reality that honey bees were in no danger of going extinct, and that the number of hives had actually been increasing for a few years. But that didn’t stop the magazine from printing this cover.

Those who demonize the “pesticide companies” should keep in mind that it’s not the companies who actually introduce pesticides into the environment—instead, it is growers, landscape managers, foresters, mosquito control agencies, and homeowners. And those applicators are not that much different from those who keep bees for a living—when we previously pesticide-abhorrent beekeepers were confronted with a pest (varroa) that threatened our livelihood, we suddenly became major pesticide applicators ourselves.

Not only that, but commercial beekeepers in many countries became pesticide scofflaws—desperately applying chemicals to protect their bees from the destructor mite, flouting pesticide regulations, and hoping that they didn’t contaminate their “natural and pure” honey to the extent that the packers would reject it.

My point: Before we go blaming others for being irresponsible with pesticides, we should first (as an industry) look at ourselves in the mirror. From that perspective, perhaps we can better understand the positions of the other stakeholders.

The above said, I’ve found that people of all stripes have a remarkable ability to rationalize whatever it takes for them to perform their job, make a profit, or maintain their style of life. So it’s not so much whether someone is right or wrong, but what the Big Picture effect is of their actions. Unfortunately for the Earth, the effect of 8 billion humans rationalizing their priorities may leave the environment and other species of life on the losing end.

So let’s start with the main applicators of pesticides…

The growers

Rationalization: it’s easy for farmers to rationalize their “need” to apply pesticides, since it’s the “norm” for their peers, and a state agency or salesman may advise them that they need to do it to “protect” their crop. (If you’re not a farmer yourself, you might want to take a look at the sort of pesticide-heavy information that they use for guidance [[1]]).

Hey, farmers gotta pay their bills. No farmer wants to lose his crop to bugs, but must weigh the cost of a pesticide application against what he/she stands to lose. And farmers have choices as to price range and overall ecological toxicity (which may not be clearly explained). Luckily, family farmers live close to the land, and generally want to protect their families and the environment. A face-to-face friendly talk along with a case of honey can really help a beekeeper to get along with his neighbors.

And if we want the growers to be more careful, we gotta show them how to profitably practice pollinator-safe pest management. We can’t just tell them to stop doing what has previously worked for them; we need to give them economically-viable alternatives to the more harmful pesticides. At the governmental and university level, we can help them by providing more demonstration projects and extension outreach to show them how to practice Integrated Pest Management, and to minimize their use of pollinator-unfriendly products.

Politics vs. Science-based Regulation

As with beekeepers, farmers are a minority in this country, and also at the mercy of urbanites. Perhaps the worst thing with pesticides is for politicians (who may know little about agriculture, pesticides, or ecology) to regulate them by fiat, simply in order to appease vociferous urban constituents. Voters can be easily swayed by scare messages, especially by well-meaning but perhaps overzealous environmental groups, or by organic marketers wanting to gain sales by painting others’ products as being dangerous to our health.

Practical application: In the E.U., several countries do not allow the planting of Bt crops, which require fewer pesticide applications. And under public pressure, some have banned some of the neonicotinoid insecticides—summarily forcing farmers to figure out other ways to protect their crops. Many feel that those decisions were based upon politics rather than science, which is hardly the best way to regulate pesticides.

We’re now trying to figure out to what extent the neonic ban cost those farmers, and whether the replacements turn out to be environmentally worse than the seed treatments. As you might expect, the Industry side is claiming massive financial losses [[2]], whereas others are treading more carefully [[3]].

On the other hand, based upon sound science, all regulatory agencies have been trying to phase out the persistent and human-dangerous organophosphates and carbamates [[4]], and California, where I live, may soon ban the most popular one — chlorpyrifos– which is the most frequently found insecticide in bee-collected pollen samples. If it’s indeed banned, farmers will need to adapt.

Speaking of California

California is the nation’s #1 agricultural state, and tends to lead the way in both agricultural practices and pesticide regulation. California voters are also quite health conscious, and leery of any chemical that could possibly be hazardous to their health.

| California’s Prop 65

Remember, I’m talking about California, in which every store that sells beekeeping supplies must warn the buyer that woodenware may be contaminated with sawdust, which under Proposition 65 is “a substance known to the State of California to cause cancer.” Ditto for that cup of coffee that you buy on the way home—it’s known by the State to contain acrylamide (which forms any time that foods are roasted). At this point, we Californians are so used to seeing Prop 65 warnings everywhere we go (such as every time we fill up the gas tank), that we just ignore them. |

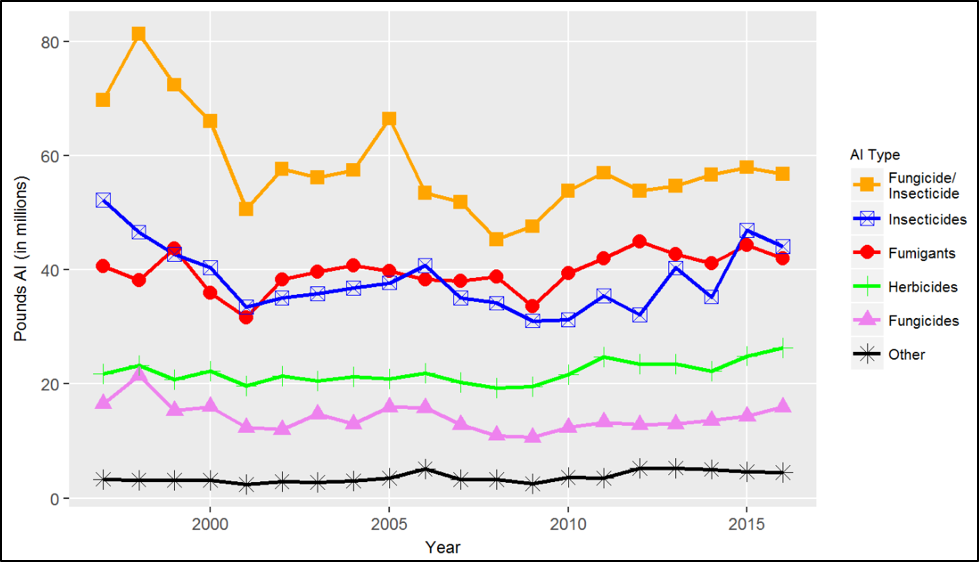

Our Department of Pesticide Regulation (CDPR) maintains a publicly-available database of all applications of restricted pesticides in the State [[5]]. Below is a sample from the 2016 summary, indicating the number of pounds of pesticides applied over time (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Wow, still a lot of insecticides being applied on California farmland! But keep in mind that the orange fungicide/insecticide plot mostly represents applications of dusting sulfur. Also note that this chart would not show any neonic seed treatments for corn. (There’s not much soy or canola planted in the State). Source [[6]].

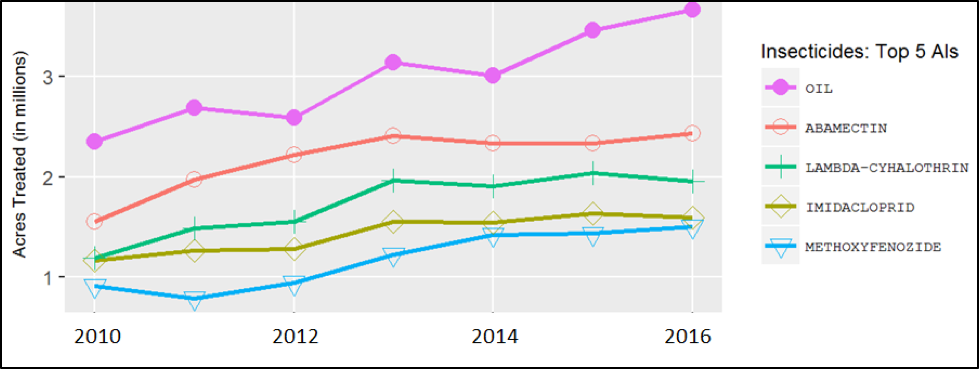

CDPR also shows how many acres those pesticides were applied to—for insecticides it was well over a pound per acre of active ingredient. This doesn’t mean that growers can’t successfully shift to safer products. The good news is that over the past 20 years, some of the nastiest “broad-spectrum” insecticides–such as the organochlorines (DDT and chlordane) [[7]], and a number of organophosphates and carbamates have been phased out, whereas inert oil and biopesticide use is increasing (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. The top 5 insecticides applied in California, as far as acres treated [[8]]. Note the trend toward using inert oils (pink). Of interest is the increased use of abamectin (red)—a “natural” and organically-certified insecticide, but still highly toxic to bees (although its residues are short-lived). Also highly toxic to bees are the pyrethroids lambda-cyhalothrin (green line; with a half-life on plants of 5 days) and the neonic imidacloprid (olive line; with an extended half-life on the surface of plants, as well as systemic absorption). Finally, the lepidoptera-specific methoxyfenozide (blue) appears to be pretty safe for bees.

Note that there are 100 million acres in the entire state of California, so the pesticides above are only applied to a tiny percentage of the State acreage. Compare that to the state of Iowa, in which 2/3rds of the state’s total acreage is harvested cropland—virtually all in typically pesticide-heavy corn or soybeans.

How About Human Risk?

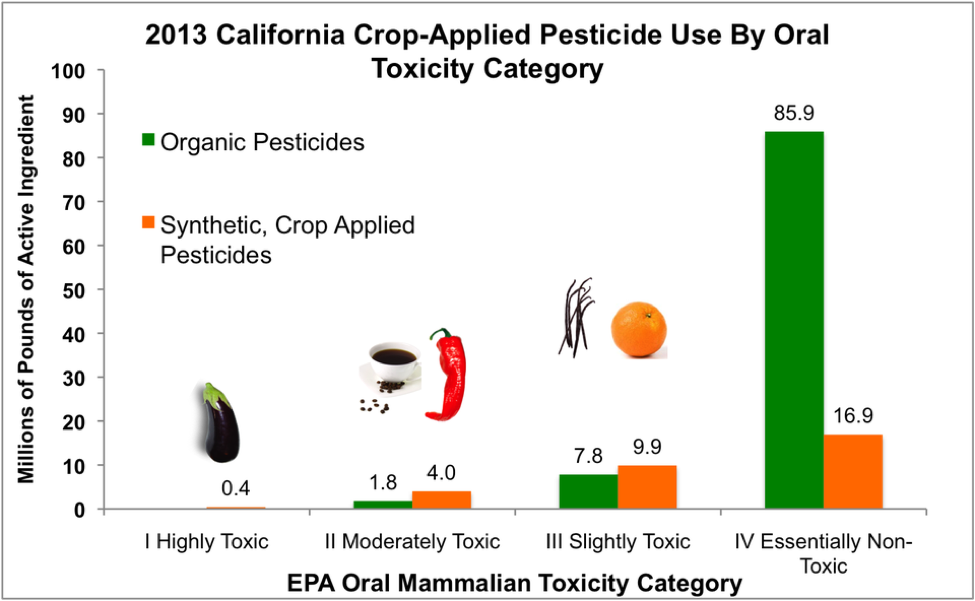

With regard to FIFRA, first in the regulators’ minds is the risk of any pesticide to “man”—meaning the consumer, the applicator, as well as those living near agricultural lands. In this matter, California is doing a pretty good job (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. This chart is from Steve Savage’s Applied Mythology website [[9]], which I highly recommend for anyone wanting to get an informed view from a knowledgeable scientist with a practical perspective on sustainable agriculture. Steve and I are both “deeply concerned about the increasingly anti-science environment in which we live today”. Check him out for his entertaining and objectively informative blogs.

Most farmers aren’t organic chemists

California’s legislature passed the Economic Poison Act in 1921, following the inadvertent poisoning of consumers by arsenic insecticides. By 1925, there were about 1,700 products marketed in California for pest control; today there are about 13,000, containing some 1,000 active ingredients. This gives growers a staggeringly-wide choice of chemistries, but unfortunately I doubt that many farmers fully understand each chemical’s ecotoxicological effects. So they often delegate the job to a Pest Control Adviser (PCA).

Pest Control Advisers

Many, if not most, growers depend upon advice by a PCA. Unfortunately, even in pesticide-strict California, one can obtain a license to be a Pest Control Adviser without any educational requirements in biology, chemistry, entomology, or integrated pest management [[10]], so long as they can score 70% in limited testing [[11]]. As pointed out to me recently, PCAs may “just follow the label,” and in almonds, may ignore the published Best Management Practices regarding pesticide applications put out by the Almond Board–thus resulting in unwarranted applications of insect growth regulators (IGRs), pollinator-hazardous “tank mixes,” or the daytime spraying of fungicides onto orchards in full bloom.

| A MODERN TALE OF THE FOX GUARDING THE HEN HOUSE: THE INHERENT CONFLICT OF INTEREST THAT EXISTS WHEN PESTICIDE DISTRIBUTORS EMPLOY PEST CONTROL ADVISERS

In California, when agricultural growers want to apply pesticides to their crops, they are required to first obtain a recommendation from a licensed Pest Control Adviser (“PCA”). Imagine you are a grower and in need of such a recommendation. A PCA visits your property to determine what type of chemical you need and how much of it is required to keep your precious crops protected from pests that could destroy your profit. The PCA tells you that he just so happens to sell the exact pesticide that he has recommended for your crop. This is a common scenario experienced by farmers, considering that nearly ninety percent of all PCAs are employed by agricultural chemical distributors and sell the very products they recommend to farmers. …This presents an extraordinary conflict of interest: PCAs employed by pesticide distributors provide pest control advice that is biased toward the profit of their employers and also aimed at earning a commission. Quoted from the San Joaquin Agricultural Law Review [[12]]. |

If a PCA is indeed practicing Integrated Pest Management, then they will sample and monitor any pest population to determine whether it is approaching the “economic injury level.” At the point where the pest density exceeds the “economic threshold” (alternatively termed the “action threshold”), control measures are implemented—one option being the application of a pesticide.

Practical application: any PCA is going to err on the side of caution (or perhaps extreme caution) so that they don’t wind up getting blamed for any minor decrease in yield. The net effect is that PCAs who also get commissions from pesticide sales may tend to advise very conservative (and pesticide-heavy) risk management rather than a demonstrated need for treatment (or alternative management strategies). On the other hand, when bee scientist Dr. Gordon Wardell was with Paramount Farms, he advised them that in their environment, there was no need to spray fungicides at all.

Along that line, the need for pollinators does give us one ace in the hole…

Pollination services (one intersection of agriculture and beneficial insects):

Back in 2004, in response to the first major short supply of bees for almond pollination, the offered rental price more than tripled. This resulted in a watershed change for the bee industry—almond pollination was now as important to the industry as was honey production. And although some emphatically blamed the neonics for the elevated colony losses during the CCD epidemic, colony numbers have rebounded, despite a quadrupling of the amount of neonics applied each year [[13]]. As pointed out by a thorough analysis by Ferrier, et al [[14]]:

“High prices are the solution to their own problem.”

Those sky-high payments offered by almond growers for pollination services became the new lifeblood of our industry, with “innovative” beekeepers ramping up their numbers of hives [[15]]. The almond growers now know the value of pollinators—that is, up ‘til petal fall. After that we gotta find somewhere else where our colonies can safely forage. That often involves other agricultural landscapes—and therein lies the rub:

Practical application: we must keep in mind that our major crops, as far as acreage planted—corn and other grains, potatoes, soybeans, and forage crops—aren’t dependent upon insect pollination, so those growers have little reason to care about protecting pollinators on their fields, other than just doing us beekeepers a favor. And if they feel that beekeepers are causing them problems, they’re likely to respond by simply kicking us off their land.

The good news is that there’s a new buzzword in agriculture: “ecosystem services,” which includes not only the pollination performed by native insects, but also the pest control benefits derived from parasites, predatory insects, and birds [[16] [17] [18]]. This is a good thing for us beekeepers, since what’s good for native pollinators and “beneficials” is also good for honey bees. In order to realize the full benefits of ecosystem services, landowners need to manage diverse habitats at the ecosystem scale, and think twice about any unintended effects from pesticide applications.

Public pressure and Voters

There is always peer pressure. No farmer that I know wants to kill pollinators. And many family farmers are proud to maintain their land in an eco-friendly and sustainable manner, often enjoying having bee hives on their property. Dayer [[19]] points out that “landowners who perceived social acknowledgement of their conservation behaviors were more likely to state an intention to persist after [participating in a conservation] program”(Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Jim and DeAnn Sattelberg received Conservation Reserve Program funding to plant “filter strips” that protect water sources on their Michigan farm. These strips can also provide pollinator and wildlife habitat, so long as they don’t receive too much pesticide drift. Photo credit USDA [[20]].

Unfortunately, at this writing it appears that the 2018 Farm Bill will reduce the Conservation Stewardship Program somewhat, and not provide adequate funding for the Conservation Reserve Program, although some pollinator health provisions may remain in place.

I’m out of space—next month I’ll continue with the future direction of pesticides in agriculture, as well as the perspectives of other stakeholders.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Peter Borst for library assistance, my wife Stephanie for her patience and proofing, and to my soft-spoken beekeeper/farmer friend Charlie Linder, who delicately sets me straight if he feels that I’ve misinterpreted anything. Feel free to check out discussions at Bee-L.

References and notes

[1] 2018 Insect Control Recommendations for Field Crops https://extension.tennessee.edu/publications/Documents/PB1768.pdf

[2] Bruins, M (2017) The impact of the ban on neonicotinoids. https://european-seed.com/2017/12/impact-ban-neonicotinoids/

[3] Kathage , J, et al (2018) The impact of restrictions on neonicotinoid and fipronil insecticides on pest management in maize, oilseed rape and sunflower in eight European Union regions. Pest Manag Sci. 74(1): 88–99.

[4] These neurotoxins are termed acetocholinesterase (ACHE) inhibitors.

[5] Pretty much anything that you can’t get at a nursery, hardware, or garden store.

[6] (Broken Link!) https://www.cdpr.ca.gov/docs/pur/pur16rep/chmrpt16.pdf

[7] I was running a farm store when chlordane’s registration was revoked. Although we hadn’t been selling it, our pesticide salesman urged us to stock up. He waxed poetic about how he sprayed his entire property with it each year, and never, ever saw any bugs.

[8] Source (Broken Link!) https://www.cdpr.ca.gov/docs/pur/pur16rep/16sum.htm#trends

[9] http://appliedmythology.blogspot.com/2015/09/a-closer-look-at-organic-pesticides-in.html

[10] (Broken Link!) https://www.cdpr.ca.gov/docs/license/min_qual_pca.pdf

[11] I haven’t attempted to take the test, but the test that I’m required to take every two years in order to maintain my Private Applicator Certificate is not challenging.

[12] https://www.sjcl.edu/images/stories/sjalr/volumes/V24N1C6.pdf

[13] As far as I can tell, CCD was the result of a perfect storm of the failure of varroa control products, the evolution of viruses, the invasion of Nosema ceranae, changes in forage opportunities, beekeepers’ failure to manage the mite, coupled with unrealistic expectations for what it takes to supply strong colonies for almond pollination.

[14] Ferrier, RM, et al (2018) Economic effects and responses to changes in honey bee health, ERR-246, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

[15] “Innovative” meaning that they stopped pointing the finger, and started controlling varroa and feeding supplemental protein when indicated.

[16] Holzschuh, A, et al (2012) Landscapes with wild bee habitats enhance pollination, fruit set and yield of sweet cherry. Biological Conservation 153: 101–107.

[17] Brittain C, et al (2013) Synergistic effects of non-Apis bees and honey bees for pollination services. Proc R Soc B 280: 20122767

[18] Pfister, S, et al (2018) Dominance of cropland reduces the pollen deposition from bumble bees.Scientific Reports 8: 13873.

[19] Dayer, A, et al (2018) Private landowner conservation behavior following participation in voluntary incentive programs: recommendations to facilitate behavioral persistence. Conservation Letters 11:2 e12394.

[20] https://www.flickr.com/photos/usdagov/18277927008/