The Pesticide Situation: Part 1

Contents

Insect populations in general 2

The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act. 4

The Pesticide Situation

Part 1

Randy Oliver

ScientificBeekeeping.com

First Published in ABJ in January 2019

I was asked to write an article focusing on pesticides and bees—a subject on which emotions run strong—but are often based upon poorly-informed opinions, one-sided views, or incomplete information. What I hope to do in this series is to help to put things into perspective.

The Earth’s Biosphere

Let’s begin by viewing The Pesticide Situation from the perspective of a “Big Picture” view (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. From this distance, what we see is the Earth’s biosphere—the thin skin on the surface of our planet suitable for life. The biosphere includes the land surface, the seas, and the lower atmosphere. Photo credit NASA [[1]].

The human population

We humans are seriously impacting Earth’s fragile biosphere. The sad fact is that there is absolutely no way that 8 billion humans can live in harmony with nature. The demands of humanity are now exceeding the sustainable carrying capacity of the biosphere–and our population continues to increase at the rate of over 200,000 additional mouths to feed per day [[2]].

We are terraforming biologically-important habitats into agricultural and urban uses, increasing the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere and the seas, and inadvertently shifting our climate to a warmer (and less life-friendly) temperature. And with regard to this article, we are also chemically polluting parts of the biosphere—which brings us to the subject of bees and pesticides.

Insect populations in general

Although honey bees are not threatened with extinction by any means, they seem to have served as a canary in the coal mine to catch the public’s attention. The reality is that insect populations in general appear to be declining across the globe. But their disappearance doesn’t appear to correlate well with either of the two usual suspects–habitat conversion or pesticides. I’ve spoken with entomologists, and it’s clear that insect species and insect biomass have been declining for some years (even before the first use of any neonics). That said, we certainly still need to pay attention to the effects of pesticides (notably insecticides) upon pollinator populations.

The agricultural situation

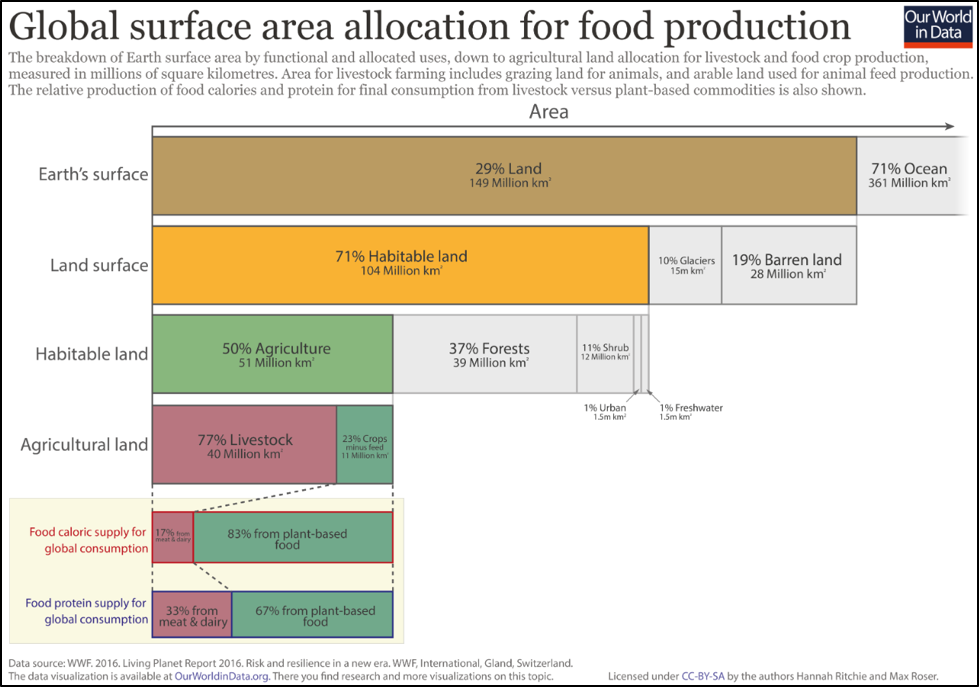

Less than three quarters of the land surface of Earth is considered “habitable”—half of which we humans now devote to agriculture of some sort; about 12% to crop production (4.2 million square miles) [[3]]. Max Roser and Hannah Ritchie have nicely illustrated the breakdown in the chart below (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. We use about an eighth of all the habitable land on earth for row and permanent crops. It is upon that portion of the land—plus a small amount for urban and suburban area—that most pesticides are applied. In the case of the U.S, roughly one fifth of all land area is classified as either cropland or urban [[4]]—neither of which serves as good habitat for most insect species. Chart by Max Roser and Hannah Ritchie [[5]].

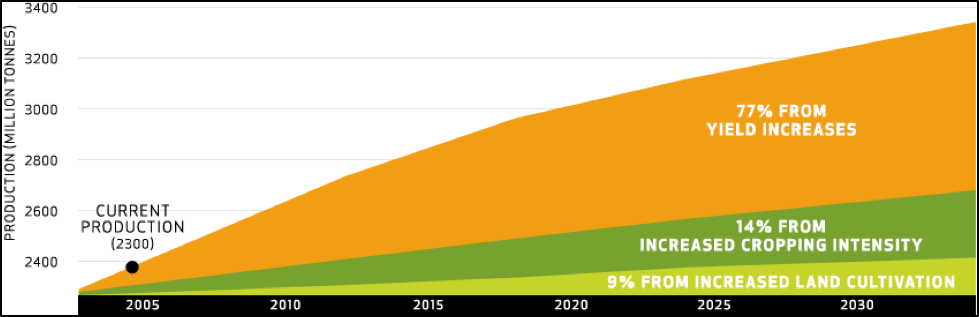

Worldwide, there are currently about 7 million square miles of land in crop production. Our current human population is nearly 8 billion, which works out to us using about a third of an acre of cropland (on average) to feed and clothe each human being. As we look to the future (Fig. 3), keep that third of an acre per person figure in mind.

Figure 3. In order to meet increased food demand, unless we want to destroy more virgin habitat (thus driving even more species into extinction), we will need to coax more and more calories and protein out of each third of an acre currently used to feed us humans. That means that growers will likely be forced to shift to higher-efficiency farming. Chart credit: farmingfirst.org.

All of agriculture is gearing up for the expected increased demand for food as our human population grows. The ever-expanding middle class calls for more meat, fruit, and vegetables. Unfortunately, the production of those desirable foods requires more acreage per calorie than for the high-efficiency crops: corn (the most efficient), wheat, rice, soy, or potatoes [[6]].

Practical application: luckily, none of those high-efficiency crops are dependent upon bee pollination, and, other than soybeans, are generally not attractive to bees. Unfortunately, the pesticides used upon these crops can still drift onto (or into) plants visited by pollinators.

Much of the Earth’s agricultural land is not being farmed sustainably, and climate change is not helping. Our current reliance on synthetic pesticides is going to change, as pests evolve and we run out of new chemistry options. The big ag companies are well aware of this, and working on more eco-friendly “biologicals,” breeding, and other improvements.

Practical application: pest management is always in a state of change, as pest species develop resistance to each new class of pesticide. Since the registration of new chemistries must now take into account their impact upon pollinators, the future is looking better for bees.

We’re unlikely to go all “organic,” since many farmers may not find the premium paid to be worth the cost [[7]]. But states like California are leading the way, greatly reducing our use of the chemicals of most concern.

The value of pollinators

What I find exciting is that the ag community is starting to realize that the pollinators are an important component of the high-value portion of the agricultural landscape.

Practical application: pollinators encompass a small group of species upon which some of our most favored foods depend—this gives them an economic value, charmingly termed “ecosystem services.” It has not gone unnoticed by activists and fundraisers that this newly-recognized economic value allows us to use the plight of pollinators to gain traction to force the ag industry to start paying more attention to the health of pollinators and the biosphere in general.

We beekeepers caught the media’s attention with CCD, and suddenly the honey bee and the monarch butterfly became the poster children for our need to start protecting pollinators. But we need to ask ourselves…

Who is the real enemy?

The short answer was well put by Pogo creator Walt Kelly: We have met the enemy and he is us (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Agriculture responds directly to the demands of the American consumer. And we give the farmers a clear directive: we want inexpensive, cosmetically-perfect fruit, vegetables, and meat. Unfortunately, the cheapest way (in the short term) to produce such perfect food requires intensive chemical-heavy agricultural practices. However, we’re learning that many of our current practices are not sustainable for the long term.

We humans are now in a position of needing to decide our place in the biosphere, and how our practices affect the survival of the other species on this planet. As far as our demand for agricultural products, we basically have only three choices:

Our three choices

- To greatly reduce the human population. This is a hard sell in the short term.

- To convert more natural habitat or grazing land into cropland. At the rate of 200,000 new mouths to feed each day, converting another third of an acre per additional human works out to at least 68,000 acres of habitat conversion per day). This would result (especially in the rainforests) in driving many species into extinction.

- To farm existing cropland even more intensively.

Although #3 perhaps sounds distasteful, realistically, it appears to be the best possible solution, and we beekeepers are likely going to have to learn to live with it. The question then is whether that even more intensive farming can allow for the existence of pollinators on that cropland.

Practical application: I’m beginning this series by trying to put things into a realistic perspective (and for us to stop blaming, and instead start being part of the solution). All farmers, large and small, are going to be pressured to intensify production. So as beekeepers, the best that we can do is to accept that fact, and push for progress in figuring out how to allow for pollinators to be an integral part of high-intensity agriculture.

One way to help pollinators in agricultural landscapes is to provide habitat and forage. The other is to minimize the number of them that are killed by pesticides. And this takes us to pesticide regulation, which falls under the purview of…

The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act

Allow me to briefly summarize the basics of FIFRA [[8] [9] [10]]:

Generally, before a pesticide may be sold or distributed in the United States, it must be registered (licensed) with the EPA. Before EPA may register a pesticide under FIFRA, the applicant must show, among other things that using the pesticide according to specifications, will generally not cause “any unreasonable risk to man or the environment, taking into account the economic, social, and environmental costs and benefits of the use of any pesticide.” I’ve highlighted three critical sections, which give a lot of wiggle room to EPA. And then EPA leaves it up to the States to enforce pesticide use regulations, recordkeeping, and reporting requirements (some states do a better job than others).

The next subject I’ll explore are the perspectives of the stakeholders involved, and what, in their opinions constitute “unreasonable risk,” “environmental costs,” and societal and financial “benefits.”

To be continued…

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Pete Borst for his long assistance in research, and to all the beekeepers, regulators, growers, pesticide applicators, ecotoxicologists, and bee researchers who have taken the time to deeply discuss aspects of The Pesticide Situation with me.

References

[1] http://antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov/apod/image/0304/bluemarble2k_big.jpg

[2] http://www.poodwaddle.com/worldclock/

[3] According to FAO definitions, arable land (row crops) accounts for 28.4% of all agricultural land (10.9% of global land area), and permanent crops (e.g. vineyards and orchards) account for 3.1% (1.2% of global land area).

[4] https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/DataFiles/52096/Summary_Table_1_major_uses_of_land_by_region_and_state_2012.xls?v=0

[5] Max Roser and Hannah Ritchie (2018) – “Land Cover”. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: (Broken Link!) https://ourworldindata.org/land-cover

[6] And also sweet potatoes, leeks, and parsnips. For some interesting reads, check out:

When farmland is scarce, will we all eat roots and tubers?

In defense of corn, the world’s most important food crop.

[7] My opinion on “organic”: I’ve gardened all my life, and resonate with the principle that organic agriculture should be based on the understanding of living ecological systems and cycles, minimal external inputs, improving the soil, and sustainability. In recent years, however, “organic” has become a marketing term for crop and animal production that meets arbitrarily-set restrictions on the use of man-made chemicals or precision-bred crops. Thus, I cannot sell my honey as “organic” since I use paraffin to waterproof my boxes.

Although I have the greatest respect for growers willing to make the effort to obtain “organic” certification, I feel that “organic” has lost its way, and is now simply a marketing term based upon fomenting fear of “chemicals” and “GMOs”—see [[7]]. As a biologist and environmentalist, this bothers me greatly. In order to feed humanity, as well as to protect the biosphere, we need to let go of some of our irrational fear that every chemical is bad (although some clearly are), and positively promote agroecology, rather than just being “anti” this or that.

[8] https://www.epa.gov/enforcement/federal-insecticide-fungicide-and-rodenticide-act-fifra-and-federal-facilities

[9] https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-federal-food-drug-and-cosmetic-act

[10] http://psep.cce.cornell.edu/issues/risk-benefit-fifra.aspx