No Negative Effect From Extended Exposure To Amitraz

No Negative Effect From Extended Exposure To Amitraz

Randy Oliver

ScientificBeekeeping.com

First Published in ABJ in July 2015

Why are we hearing of elevated rates of queen loss and poor survivability of colonies these days? Could it have anything to do with sublethal effects of the commonly used miticide amitraz?

Introduction

Last spring I ran a field trial in order to determine whether treating nucs with Apivar (active ingredient amitraz) strips would affect their buildup. The results (that there was no observable effect) were published in this Journal in October 2014 [1]. But by that time I had further researched amitraz, and was curious as to whether its residues (primarily DMPF) had an adverse effect upon colony or queen health and survival [2]. Since I already had 36 colonies that had been continuously exposed to treatment with Amitraz, I decided to continue the trial to see if there were any long term effects.

Funding sources: I hope to be reimbursed for this trial by a grant from the North Dakota Department of Agriculture, solicited for me by the North Dakota Beekeepers Association.

Materials and Methods

The 36 colonies had been previously started on June 4, 2014, paired by sister queens, with one hive of each pair receiving an Apivar strip on July 1 (which ensured continual release of amitraz, and buildup of DMPF residues in the combs). At the end point of that trial on August 8 there were no significant differences between the Test and Control colonies.

On September 1 &2 the honey flow had ended, but there was still mixed pollen coming in. A few colonies contained beebread, but most were living hand to mouth. All had active broodnests and no sign of nutritional stress. We marked all the queens with paint (Fig. 1), and replaced the existing Apivar strips with new ones to ensure continuous exposure to amitraz. We then fed all colonies equally with pollen sub patties and sugar syrup for the next few weeks.

Figure 1. Finding all the queens for marking was no fun. We needed to shake some colonies through a queen excluder “sieve box” to do so. We lost 2 queens due to injury during the process, and requeened those hives with sister queens. We breed for “gentle” bees, and can normally work with minimal protective gear.

We also took mite washes of 6 arbitrarily-chosen Control colonies (counts were 2, 3, 4, 0, 2, and 39 per half cup of bees—all save one were at or below a 1% infestation). The single high count was of concern, so we treated all colonies with Hopguard II the next day, and again two weeks later.

Scientific consideration: Managing varroa in the Control colonies was a challenge: the Apivar was controlling varroa in the Test hives, but I couldn’t allow varroa to build in the Controls. Whatever I did to the Controls, I had to also do to the Tests. So I was layering another miticide on top of the amitraz. Therefore I was limited to treatments that wouldn’t be expected to synergize with amitraz—such as Hopguard. Unfortunately, Hopguard is not very effective when colonies contain brood. I had hesitated to use thymol (Apiguard) since there was a report that both it and amitraz might both exert action on the bees’ octopamine receptors [3]. However, a recent study did not find evidence of synergy [4].

On September 29 mite counts were acceptable (below 2% infestation). But due to high mite pressure that we were seeing in our other yards, we treated all hives with ~25g of Apiguard on an index card. The colonies were looking good, but only one colony had brood in the second box of foundation, so we replaced any remaining foundation with recently extracted sticky drawn combs, and fed heavy syrup and swapped honey combs to equalize winter stores. We also fed another pollen patty.

On October 3 mite levels were still below 1%. On November 26 we hit varroa hard with a combination of ~25g of Apiguard plus an oxalic dribble [5]. The colonies were not very strong, averaging about 8 frames of bees. There were no noticeable differences at this time between the test pairs.

On December 22 we fed a pollen sub patty and swapped the Apivar strips for new ones. On January 5 I graded all the colonies for strength, and then fed ½ gal light syrup. On February 5 we moved all live colonies to an almond orchard.

Practical problem: As commercial beekeepers, sometimes beekeeping gets in the way of science. Demand for moving our hives to almonds came early, and things were beyond hectic. At this point in time we misplaced our notes as to which colonies were removed from the trial due to lack of strength. Upon return from almonds we could not locate 5 of the hives (3 Control, 2 Test), so I assumed that they were removed from the trial on Feb. 5.

On March 10 we moved the hives back home, and allowed them to continue to build up on natural nectar and pollen flows. On April 2 I performed the final grading for strength before any of them swarmed.

Results

Upon return from almonds, and at final grading, all colonies were queenright save for one in the Test group. Additionally, the Control colony that had previously had the high mite count had dwindled to only 1.5 frames of bees; I redacted these two colonies from the data set. Although I had planned to check all colonies to confirm that they still contained marked queens, other pressing bee work at that time did not allow me to do so. However, it is unlikely that any of the queens had been superseded since marking them in September, since there are few drones present over winter in this area.

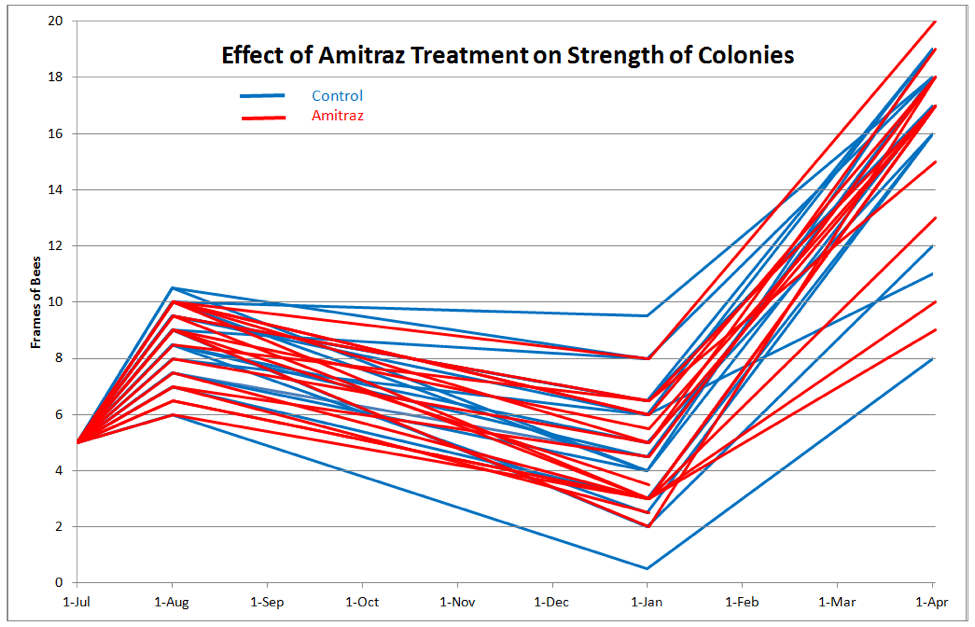

At final grading, the colonies ranged in strength from 8-20 frames of bees. There was no apparent or statistical difference between the groups (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Colony strengths over time. There was no difference in colony strength or survival due to continuous exposure to amitraz.

Discussion

Despite being continuously exposed to slow-release amitraz (applied as Apivar strips three times over the course of 8 months), we could see no difference in colony buildup, overwintering success, or queen survivability due to treatment. We also found Apivar to be effective at controlling varroa levels.

Although I did not confirm the actual residue levels of amitraz or DMPF in the combs by chemical analysis, previous research [6] suggests that levels would have been substantial, based upon the rate of application versus the numbers of combs covered with bees for most of the duration of the trial.

The results of these two combined trials indicate that treatment with Apivar at the manufacturer’s recommended rate appears to be a safe and effective tool for varroa management.

Citations

[1] https://scientificbeekeeping.com/effect-of-amitraz-on-buildup-of-nucs/

[2] https://scientificbeekeeping.com/amitraz-red-flags-or-red-herrings/

[3] Blenau, W, et al (2012) Plant essential oils and formamidines as insecticides/acaricides: what are the molecular targets? Apidologie 43:334–347.

[4] Johnson RM, Dahlgren L, Siegfried BD, Ellis MD (2013) Acaricide, fungicide and drug interactions in honey bees (Apis mellifera). PLoS ONE 8(1): e54092

[5] 5 mL/seam of bees, 3.2% w:v as per https://scientificbeekeeping.com/oxalic-acid-treatment-table/

[6] For references, see https://scientificbeekeeping.com/amitraz-red-flags-or-red-herrings/