The Extinction of the Honey Bee?

The Extinction of the Honey Bee?

Randy Oliver

ScientificBeekeeping.com

First Published in ABJ in July 2012

We call on you to vote to stop production and sale of neonicotinoid pesticides until and unless new independent scientific studies prove they are safe. The catastrophic demise of bee colonies could put our whole food chain in danger. If you act urgently with precaution now, we could save bees from extinction [1].

Your signature may be all that stands between bees and their extinction [2].

Well, I hummed and hawed, and didn’t sign the petition. And now I’m feeling the shame and guilt of worrying that I’m party to causing the extinction of the honey bee. Just imagine—the world would starve to death, I’d have to find a new line of work, and this magazine would go belly up!

And now I read that “In the last few weeks beekeepers have reported staggering losses in Minnesota, Nebraska and Ohio after their hives foraged on pesticide-treated corn fields”[3]. Oh my gosh, is the honey bee actually in danger of imminent extinction?

Scientific Skepticism

Folks, I did high-country surveys which documented the slow extinction of the Mountain Yellow Legged Frog in my area of the Sierra Nevada. I knew the last remaining frog’s favorite rock upon which he’d be sitting, until one summer, he was gone too. Extinction is final, and the term is not something to be bandied about lightly.

A key aspect of the scientist is that he is annoyingly skeptical about anything that anyone tells him, and in truth I take this “extinction of the bees due to seed treatments” story with a grain of salt. It’s an alluring story to be sure, and some beekeepers have repeated it so many times that they view every single bee health problem through neonicotinoid-tinted glasses. The problem is, that to a scientist, during the telling of the story, red flags keep going up—things don’t quite fit together right, and after a bit a questioning, the story may not quite have the same ring to it. And when I’ve further investigated many cases in which beekeepers blamed pesticides for deadouts, I’ve often found that more usual causes, such as mites, viruses, nosema, or poor nutrition were the more likely culprits.

Until recently, I’ve intentionally avoided addressing CCD and pesticides directly, since they are such emotionally-charged topics. But I must admit, I was not ready for the degree of flak and criticism that I’ve recently gotten for what I feel is objective questioning and reporting! There are some who have tried to suppress what I publish or say, or who are determined to try to paint me as some sort of shill for Bayer.

Be assured that it is not only beekeepers of whom I am skeptical. I’m skeptical of anyone and anything connected with the companies that produce or sell pesticides. I may have been born at night, but I wasn’t born last night! The PR flacks that the pesticide companies hire for their greenwashing could make it sound like the Chernobyl nuclear disaster was a good thing for the environment because it created a new wildlife preserve!

I live in a world of hard reality, and I’m a tough person to converse with if you can’t back up everything you say with facts and evidence–I have a reputation for challenging unsupported opinions (to the considerable annoyance of some beekeepers and scientists). But I do go out of my way to be objective, and to not to take sides or positions—I just want to get to the truth of issues.

So I’m going to put my current series on hold for a month, and skeptically investigate the whole “seed treatments are going to cause the extinction of the bees” claim.

Planting Dust

Beyond Pesticides has recently made much of a “new route of exposure [for bees to neonicotinoid insecticides] through seed planter dust.” Sure, Drs. Krupke and Hunt (2012) recently confirmed that the dust from pneumatic seed planters contained toxic insecticide residues, but the finding was hardly “new.”

In actuality, the problems with planting dust have been well known since an incident in Germany in 2008, when the use of a faulty “sticker” on treated seed resulted in the drifting of dust that caused serious mortality in thousands of bee hives downwind. To their credit, Bayer stepped up to the plate and immediately started writing out checks to the affected beekeepers to cover their losses. Germany temporarily rescinded the registration of clothianidin for seed treatment.

The incident was a public relations disaster for Bayer; it doesn’t take a genius to figure out that they did not want a repeat! So the chemists and engineers thoroughly investigated different stickers and modifications of the planters to try to make the planting method safe for bees. There has been a great deal of excellent European research on the subject (Apenet 2010).

Girolami (2011) trained bees to fly through clouds of planting dust tainted with various seed treatments. They found that bees indeed became coated with insecticide particles; after repeated passes through the cloud over the course of an hour, they could accumulate up to 25 times the theoretical lethal dose of neonicotinoid. Yet surprisingly, few died unless humidity was artificially kept to above 95% RH! At lower humidities, it appeared that bees could generally groom off the dust without poisoning themselves. They concluded that:

“The scenario of the deaths of bees at the time of the maize sowing could be linked to the normal repeated flights of foraging bees to meadow flowers… When bees fly near the drilling machine at a height of about 2 m [about head height], they get powdered with a high quantity of insecticide with lethal consequences when the humidity is high….[but] it should be noted that if extended monocultures of maize are present, with consequent lack of flowers in spring, bees would not normally cross these large areas and thus avoid contamination….Bees in the field seem to tolerate a relatively high powdering with neonicotinoids; this means that is not necessary to completely stop the powdering, instead it would be opportune to reduce the contamination below a probable level that incurs bee deaths” (emphasis mine).

Planting Dust Problems in the Corn Belt

After reading the European bee research literature, I fully expected planting dust to at least be an occasional problem in the U.S. And with a record 95 million acres of corn being planted this year, bees should be dropping like flies (sorry for the lame pun). So when in May I began to hear reports of bee mortality due to planting dust, it made me curious as to the degree to which that dust was actually affecting bees. Unfortunately (or fortunately for me) I don’t experience planting dust issues first hand, since I’ve moved my bees to corn and alfalfa only after the corn was planted. Planting dust issues should be fairly easy to investigate though, since they should occur immediately after an easily documented event—a field being planted—and there should be easily observable dead bees on the ground!

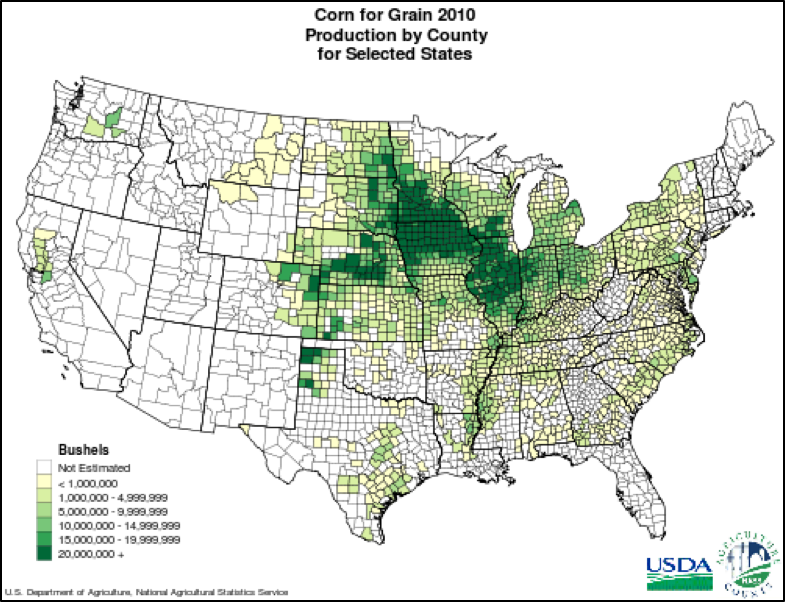

So I took advantage of a speaking engagement that I had with the Michiana Beekeepers Association to get a whirlwind tour of apiaries in the eastern part of the Corn Belt (Fig. 1)—not far from where Krupke (2012) documented bee mortality associated with corn planting dust in previous years.

Figure 1. I wish to thank my hosts in Michiana for showing me around apiaries in the Corn Belt. This is the area in which clothianidin (Poncho) is most widely used as a seed treatment, and would presumably be ground zero for the extinction of the honey bee due to heavy use of that insecticide.

Report from Ground Zero

Corn planting was underway when I arrived in Indiana (Fig. 2). When I questioned my ride, beekeeper Bob Baughman, about bee mortality, he confirmed that some beekeepers were having serious problems with either planting dust or winter mortality. I’ve seen bee kills due to pesticides, and I was eager to document such “incidents,” since EPA had gotten virtually no reports in previous years of problems with clothianidin–the only incident report filed for this pesticide as of August 2010 was filed by yours truly! (That must have been prior to me becoming a lackey for Bayer).

Figure 2. Farmers were still actively planting corn when I recently visited Indiana. My appreciation to my host Danny Slabaugh for helping me to find one still at work on a late Saturday afternoon.

Bob handed me off to my host, beekeeper Danny Slabaugh, who took me to inspect several apiaries belonging to him or beekeeper Tim Ives. We checked the ground in front of the hives, and sure enough, there were a few slowly crawling or freshly dead bees in front of most of the hives. Danny observes that the number of dead bees goes up during planting for a few days–I saw as many as a few dozen recently dead bees in front of hives (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Dead and dying bees on the landing board of a nuc in Danny’s home yard. This seemed to be fairly typical after planting—a few dead bees for several days. I checked two 10-bee samples for nosema—the levels were trivial, so in this case I could eliminate nosema as a suspect. Photo credit Danny Slabaugh.

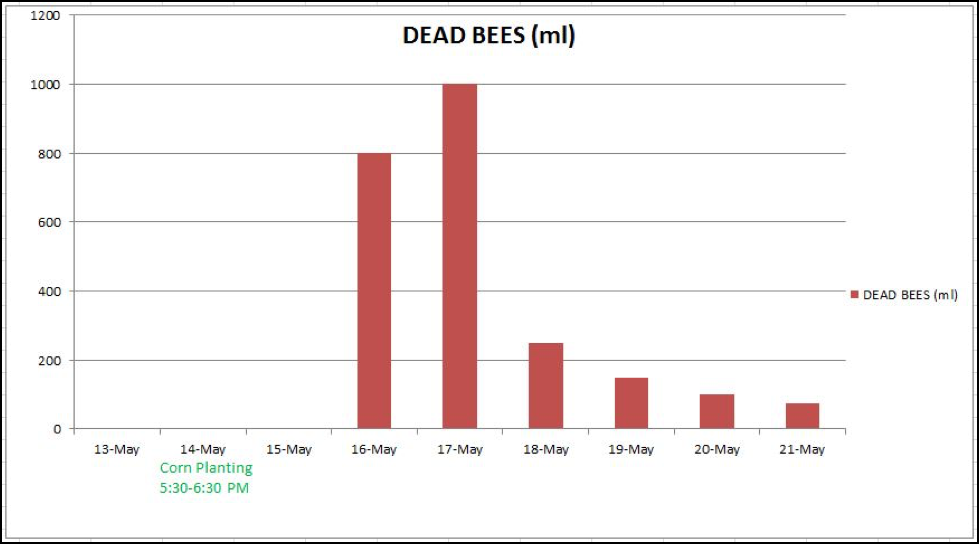

I’ve been corresponding with a hobby beekeeper in Madison County, Indiana who was willing to collect some data for me (and who, like many of those I’ve spoken with, begged to remain anonymous, not wanting to have to deal with any flak). He keeps four hives of bees over a concrete pad, so I asked him to measure the number of dead bees swept up each day subsequent to the planting of corn in an adjacent field. He graphed the data just in time for deadline (Figure 4):

Figure 4. Bee mortality data from 4 colonies after corn planting as close as 260 ft from the apiary—for a total of 160 acres of corn in total planted within 1000 yards of the hives. At the time, bees were working Tulip Poplar, Black Locust, Dandelion, early clover, and suburban flora. There are roughly 3 bees per ml, so the highest mortality count was about 750 dead bees per hive per day (not counting any lost in the field)—a substantial short-term mortality, but in perspective, less than the number of eggs the queen laid on any day.

Of note is that the beekeeper also sent me videos of the hive entrances on 21 May; he made the point that all the colonies remained very active. On 24 May he said, “I was in the hives this afternoon and all the colonies are strong. The number of dead bees is back to normal.” Something of interest to me was his comment on a photo that he sent (Fig. 5) that the dead bees largely appeared to be young bees, something that Danny had also pointed out.

Figure 5. Dead bees in front of the hive on 18 May. Surprisingly, more than one beekeeper noticed that the dead bees were often young, grayish, freshly-emerged bees. I also noticed that many of the dead bees are “small”—I don’t know what’s up with that!

Why would freshly-emerged bees be dying? Dust wouldn’t be expected to penetrate the cappings. So their untimely death suggests that they are being hit immediately after emergence. Since newly-emerged bees can’t even fly, then that suggests that they are being exposed to the pesticide(s) within the hive, and since they die at a disproportionate rate, that they are more susceptible to the pesticide than the older bees!

How would they be thus exposed? Given that flying foragers build up an electrostatic charge that would cause contaminated dust to stick to them, and since the pesticide dust does not kill them quickly, they may inadvertently carry high levels of pesticide back to the hive. Three possibilities (or a combination thereof) then come to mind.

- Newly-emerged bees come into contact with returning dusted foragers when they cross paths in the brood nest.

- The foragers might groom the dust off their bodies and inadvertently incorporate it into their pollen loads. Since newly-emerged bees immediately seek a meal of the fresh pollen stored around the broodnest, they could conceivably consume a lethal dose. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the “small” dead bees collected from the front of the hives had pollen in their guts.

- Perhaps a newly-emerged bee has not yet fully developed its capability to degrade pesticides, and may simply be more susceptible to any pesticide input into the broodnest environs.

In any case, these would all be considered as acute bee mortality issues, not sublethal effects. The timing of the planting wouldn’t have allowed the pesticide to have had an impact on those young bees prior to their being capped over. The patterns of sealed brood looked good. It appeared that there might have been a bit of mortality of the very young brood. This is of interest, as that is more typically an effect of fungicides; clothianidin is virtually nontoxic to bee larvae (Lodesani 2009). But I didn’t think at the time to more rigorously investigate this (funny what you think of after the fact).

What was really odd was that when I picked up the dying bees, they did not exhibit the typical symptoms of neonicotinoid poisoning (Fig. 6)—there was no trembling, and the bees could right themselves when I rolled them onto their backs. So I’m not even sure that it is the neonicotinoid treatment alone that is causing mortality; it could perhaps be one or more of the other components of the dust, perhaps in combination. We’re just going to have to wait to see the various test results.

Figure 6. I picked up dying bees from in front of hives. Oddly, they did not exhibit the typical symptoms of neonicotinoid poisoning—they were not trembling (neonics are stimulants), their tongues were not necessarily extended, and they were able to right themselves if I rolled them onto their backs. Krupke (2012) found clothianidin to be associated with all dying bees, but also found residues of fungicides and herbicides, so the toxicity issues may be complex!

In none of the apiaries could I find the piles of dead bees that I had envisioned. How could this be? I downloaded the recent weather history for South Bend [4]—it had been running between 20-60% RH (it still seemed muggy to this Californian!). Perhaps this was a clue—maybe planting dust was only an issue if humidity was sky high. But this doesn’t jibe with Dr. Hunt’s observation of bee deaths under dry and dusty conditions last year—so I’m at a loss to explain.

OK, so how about those toxic droplets of guttation fluid on the corn seedlings? Danny and I walked the rows of emerging corn glistening with guttation droplets in the dry afternoon, next to one of his apiaries (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Droplets of guttation fluid on young corn plants. These droplets may contain high levels of neonicotinoids. But I did not observe any bees working them on a warm, dry afternoon, nor could I find any dead bees on the ground in the field, despite a few hives being close nearby. This is the same result as I’ve seen in other studies (e.g., Apenet 2010).

The apiaries that I visited mostly had freshly-planted corn and soy nearby (Fig. 8), but also generally a bit of pasture or woods, which these beekeepers understandably favor as apiary locations, since they contain a wide variety of flowering plants (as compared to the corn/soy deserts). There was a good nectar flow on from Dutch clover, brambles, and assorted bloom. Both beekeepers were building up plenty of strong splits, and neither was particularly concerned about the relatively small degree of bee mortality.

Figure 8. Typical view from one of Danny’s apiaries overlooking corn. There was absolutely no bee forage in the planted corn or soy areas at this time of year, so the bees were working nearby pastures, untilled strips of clover and weeds, and patches of woodland, which comprised about half the acreage within foraging range.

One thing about Indiana is that there are areas farmed by Mennonites and the Amish, who tend to eschew pesticides and practice more rotation of their land into pasture. Oddly, when I inspected the area in front of hives for dead bees, I couldn’t detect that there was any trend for there to be less mortality in the low-pesticide areas as compared to the high-pesticide areas. Things just weren’t making sense! And I kept seeing bumblebees, native bees, and butterflies—all species that I would expect to be decimated by the massive pesticide use all around. When I asked, some told me that they see fewer native pollinators than in the “old days,” but I don’t know whether that is a pesticide issue, or due to lack of forage with the recent change to wall-to-wall no-till farming.

At the meeting at which I spoke, attended by about a hundred mostly hobby local beekeepers, I asked for reports of pesticide problems, and a number of beekeepers spoke with me. The local beekeepers had the usual problems with varroa, poor forage, and wintering, but few laid blame for their problems on pesticides. When I asked for a show of hands for those who had ever had their bees tested for nosema, none went up.

I had lunch with Dave Schenefield and Bob Baughman, both of whom had suffered from more serious bee kills at planting, but at sites too far from the meeting for me to visit. I asked them to send me photos (Fig. 9). I had put Dave in contact with Bayer last season when he told me that he had been having planting dust problems, and they were investigating his kill this spring. Dave told me he was satisfied with their response, and expected results from the testing of his dead bees within a week or two (Bayer generally sends half the sample off to an independent lab to confirm their own tests).

Figure 9. A close up of a substantial bee kill due to planting dust in one of Dave Shenefield’s apiaries. This apiary suffered a serious setback due to the loss of a large proportion of the adult bee population. Oddly, Dave told me that the strongest hives were more affected than weaker hives—perhaps because they had more foragers exposed to dust? Dave expects these colonies to recover, but he has essentially lost all nuc sales or the expected honey crop from them—a real hit to the profitability of his operation. Photo Dave Shenefield.

I really wanted to take photos of dead bees on the ground myself, but we couldn’t find anyone locally who had experienced serious bee kills. I asked Bob Baughman to check his Michigan yards in which he had experienced die offs last season. Although there had been intense planting around those yards this year, he did not find any serious mortality. But he did describe the symptoms that he observed last season after exposure to planting dust:

- Bees fly up to the hive and bounce off the hive face

- Bees crawl in the grass and away from the hive

- Queen dies at some point in the 60 days after planting

- The hive dwindles down leaving all the honey stores untouched

- No bees can be found in the hive…nothing, no larva or dead bees

I was unable to confirm such symptoms, but have no reason to doubt his observations. Bob also tells me that he observes serious bee mortality after farmers spray herbicides.

Other States

I thank the Michiana beekeepers for sharing their experiences with me. Clearly, the pesticides involved in corn planting are an issue there, although a decidedly minor one for most of the beekeepers with whom I spoke. But did the same hold true for other states? Kim Flottum reports that he is being flooded by reports of bee kills in Ohio [5]. Bob Harrison suffered a loss of the major part of the field force at corn planting in an apiary in Missouri, and some beekeepers have contacted me about problems in Canada.

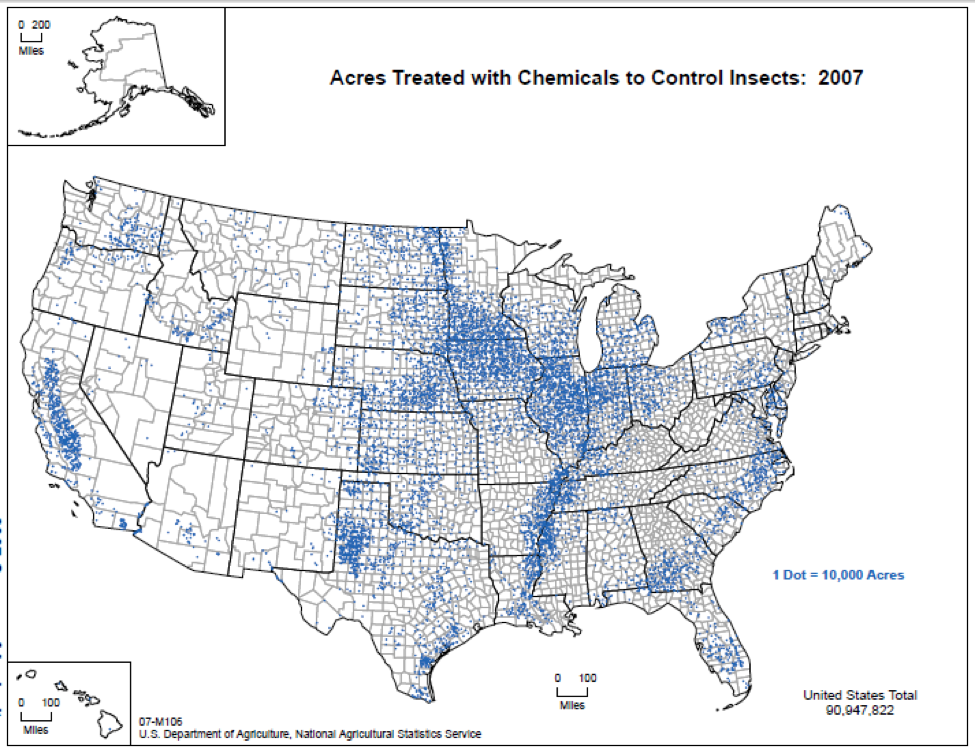

When I’m trying to figure something out, I generally look for the most extreme examples. So I downloaded figures from the National Agricultural Statistics Service in order find out where in the U.S. that bees would be subjected to the most intense exposure to planting dust. I found that, incredibly, two out of every three square feet of soil in Iowa and Illinois is planted to either corn or soybeans! The vast majority of these two crops are planted with neonicotinoid-treated seed. Clearly, this would be ground zero for bee extinction (Fig. 10).

Figure 10. The proportion of insecticide-treated acres in Iowa and Illinois is staggering! If pesticide application is indeed causing the extinction of bees, surely one should be able to witness it here!

Surprisingly, both of these states have numerous active beekeeping associations, so I contacted beekeepers and state apiculturists and asked how the bees were doing, and whether they were having problems with planting dust. Typical responses (names withheld to protect the innocent):

Iowa: Randy, I’ve got 90 locations in the Iowa corn areas. This year is as good as it’s been in 20 years! I read about Krupke’s paper, but I just don’t see it—I don’t have any problem with the insecticides used on corn. Maybe other guys have had problems under conditions of a “perfect storm” situation, but I’m not hearing of it.

Illinois: Randy, I don’t believe there has been a problem with dust in central Illinois. My bees have never been stronger going into spring and I have not witnessed a death loss due to chemicals. Swarms have been prolific and we have had an excellent honey flow. I have had bee kills in the past from aerial spraying of corn fields for Japanese Beetle using Sevin as a control.

Illinois: There has not been a single report filed with the state this spring for any bee kills.

A number of the respondents expressed uneasiness about the amount of pesticides being used, but it surprised me how adamant most were that the pesticides on corn didn’t seem to be causing problems! How could this be? Either every beekeeper that I spoke with was delusional about having great bees, or Bayer has somehow managed to brainwash all the beekeepers in those states, or, incredulous as it may seem, perhaps the seed treatments weren’t generally causing serious problems.

Surely I was missing something! So I downloaded the per-hive honey yield figures for Iowa and Illinois for 2011, figuring that pesticide-stressed colonies would be unable to produce surplus honey. Incredibly, Illinois and Iowa ranked right in there with North and South Dakota! When I asked beekeepers there how they made so much honey off of corn and soy, I found that they do the same thing that the Indiana beekeepers do: look for pockets of untilled land and hilly areas as reserves in which their bees can forage when there is nothing flowering in the corn and soy fields.

OK, so reports of serious problems due to planting dust remained largely elusive to me. I’m waiting to see the results of the ABF survey of beekeepers [6], and other reports to get a better idea of the actual extent of serious bee mortality due to planting dust. Please note that I am only discussing planting dust here—beekeepers are all well aware of the potential for serious bee kills from any of several different pesticides sprayed later in the season. With the price for soybeans being so high, farmers are going to be spraying more insecticides than usual. One knowledgeable beekeeper/grower is predicting that this may be a tough year for bees near soybeans!

Success Stories

I can’t stop thinking about that annoying enigma—the successful beekeeping by Danny and Tim (and many others) in the midst of pesticide-laden fields of corn and soy (Figs. 11 and 12). How could that be? Each of these beekeepers runs over 100 colonies. Danny runs part of his operation for honey, and uses the other part to produce a large number of nucs for sale. Tim has expanded from 15 hives to about 150 over the past few years. Neither has winter losses above the national average of 30%, and in some yards they had 100% survival. But that ain’t the half of it. Not only do their bees have to deal with pesticides, but neither beekeeper uses any treatments against varroa or nosema–both going on seven years (be careful if you attempt this yourself)!

Figure 11. Danny Slabaugh showing me a comb drawn since corn planting in an adjacent field. His colonies appeared to be thriving, not only despite the pesticides, but without any treatments whatsoever for varroa in the past seven years!

Figure 12. Tim Ives with some of his hives in Liberty, Indiana, at a large apple orchard that is sprayed with the neonicotinoid Assail three times a season (the spray also falls on the lush growth of flowering clover and weeds under the trees). I checked the location on Google maps, and could see that roughly half the land area for two miles around was planted to corn and soy. These colonies each produce around 300-400 lbs of honey, while drawing out supers of foundation!

How do they do it? Both seek out apiaries with some sort of woods, pasture, or uncultivated area nearby, to give the bees access to forage other than corn and soy fields. Both run mite-resistant bee stock. Danny has brought in various breeder queens, and grafts from them. Tim collects swarms and breeds from survivors by simple splitting. Tim winters with plenty of honey on the hives; Danny feeds hard sugar blocks and uses windbreaks. Both keep apiaries on the edges of, or inside, small acreages of woodlands. Neither one complains about pesticides, even though I could see vast fields of corn and soy within a stone’s throw of every apiary! Tim suggests that perhaps by him selecting his stock solely from local “survivor” colonies, that he might be breeding bees that are resistant to the local pesticides!

Beekeeper-Grower Cooperation

Tim took me to a beautiful apple orchard where I met the owners, who take pride in working with the beekeeper, shutting off the sprayer when they get next to Tim’s hives to avoid bee kill (they spray Assail 3x a season).

I consider this sort of cooperation between beekeepers and growers to be an excellent example of the stakeholders working together to get along. The beekeepers that I spoke with understand that the farmers need to make a living, and say that the farmers don’t want to kill bees. Couple this attitude with programs such as Driftwatch, new generations of reduced-risk insecticides, and improved label restrictions, and I see a future for both beekeeping and farming. OK, I know that sounds corny as hell, and we’re not going to get there without problems. But I’m pretty inspired after visiting these successful Indiana beekeepers!

My Take on the Situation

Please correct my reasoning if I’m wrong, but it seems to me that if clothianidin and planting dust were half as devastating to bees as some make them out to be, that you’d think that those keeping bees in the middle of the areas of heaviest application would have noticed, wouldn’t you?

Given that, it appears to me that the reality of the situation lies somewhere between the pesticide companies’ warm and fuzzy assurances that their products are gentle on bees, and the activists’ claims that pesticides are causing the extinction of the bee. It appears that under “normal” conditions, with properly-outfitted pneumatic seed drills, that the impact of planting dust is minimal. It does appear that there is often minor bee loss shortly after planting. On the other hand, although I didn’t see it with my own eyes, I do not doubt that on occasion planting dust does indeed cause serious bee kills.

When a beekeeper, such as Dave Shenefield, does indeed suffer from a pesticide kill, then we need to get all agencies plus the pesticide manufacturer involved in order to (1) give the beekeeper some recourse for financial compensation, and to (2) figure out what went wrong so that it doesn’t happen again!

I simply don’t see an outright ban on clothianidin happening—too many beekeepers are happy as clams that they can keep bees in corn these days without the devastating kills of yesteryear. I also see that we need to put our fingers on the specific factors that do come together in certain situations to cause beekeepers serious losses:

- The planter model and filtration. The Europeans have standards for dust emission; the U.S. doesn’t.

- The adhesion and thickness of the stickers. Better formulations, when they abrade, create larger particles that drop to the ground, rather than being dispersed as dust.

- The influence of the relative humidity of the air. Girolami found that it took high humidity for the active ingredient to cause bee mortality. On the other hand, I hear of more problems with planting dust under dry conditions.

- Brett Adee tells me that planting dust seems to be less of a problem when the soil is moist—perhaps the residues stick to the moist soil as it is disked up.

- In some cases, farmers seed directly into flowering clover, rather than burning off the cover crop first with herbicides. This might put concentrated pesticide right onto the bloom, and suggests that the label needs to be changed.

Even though affected colonies generally recover, they may lose their critical “momentum.” The beekeeper deserves to be able to recover damages. For all I know, the dead bees on the ground in front of the hives may only represent a fraction of those bees actually lost to the pesticides.

In general, I find that beekeepers mostly seem to want to work with farmers in return for locations, are willing to take little losses, and generally don’t want to rock the boat. But no one can absorb significant losses year after year!

I do have some skepticism about some beekeepers’ claims. Clearly a late-summer hit with a bee-toxic pesticide will guarantee high winter mortality. But I’m having a difficult time buying that a hit with planting dust in May then causes high winter mortality seven to nine months later. I suspect that other factors are involved. There are a lot of other chemicals sprayed on corn and soy during the season, and a focus solely upon clothianidin distracts us from research on the impact of those chemicals upon bee health.

I have trouble with beekeepers who blame all their problems on pesticides, since I myself have plenty of problems in my own operation, and my bees have virtually no pesticide exposure! These beekeepers lose credibility when they ignore the often major impacts that poor nutrition, varroa, viruses, and nosema have on stressed commercial colonies.

What’s Going to Come of This?

This season the EPA will finally be getting the reports from beekeepers that they’ve been asking us for. The various investigatory teams (state, university, and industry) that took samples from affected apiaries will be publishing their findings. I’ve heard some of the preliminary results, and I have every reason to believe that the pesticide companies will own up to the fact that in some cases planting dust is indeed killing bees. In other cases, factors as straightforward as AFB or nosema were being overlooked.

In a best case scenario, the chemical companies that sold the responsible products will investigate the incidents (I know that Bayer is), and determine what caused the problem. The EPA will then, forced by public pressure, either tell the companies to fix the problem, or revise the label.

Most affected beekeepers will likely be happy with a resolution that simply acknowledges that there is indeed a problem, and that the agricultural industry and EPA are actively working to solve it. Some may file suit to collect damages, as would any grower whose crop or livestock were injured by pesticide drift from neighboring landowners. If there are monetary damages awarded (I was hired by an insurance company two years ago to confirm such damages), that will really get the applicators’ attention! I strongly support an occasional lawsuit to keep everyone in line, and have pledged cash toward a beekeeper defense fund.

I may be overly optimistic, but I’ve got the feeling that we are going to be moving in a positive direction this year toward resolving planting dust problems!

The Big Picture

Our agricultural system is still far too dependent upon pesticides! With corn and soy at all-time high prices, farmers no longer practice pest management—they practice “risk management” by blindly using far too many treatments, far too much of the time. This is a good time to be a pesticide salesman! Indeed, it may be difficult for farmers to even buy pesticide-free seed [7].

There is no reason to treat every seed with pesticides—this inevitably leads to the development of resistant pests, and unnecessarily adds to costs. Plus, many of us are concerned about the potential buildup of these pesticides in the soil. Integrated pest management that involving monitoring and crop rotation are more sustainable strategies. Gratuitous pesticide spraying poisons all sorts of “off-target” organisms, and is self perpetuating–putting the poor farmer on a never-ending pesticide treadmill [9].

I was impressed by the beautiful Amish and Mennonite farms, with cattle on pasture, crop rotation, and minimal pesticide use. For the life of me, I can’t say that I consider the ugly scars of the face of this planet that we call “modern agriculture” to be an improvement! Oops, I just let my “inner environmentalist” slip out—sorry! But when one comes back from seeing successful beekeepers who never need to treat their hives, and farmers who live in relative harmony with Nature, I see models for the future.

The future lies in moving toward “agroecology”: the application of ecological science to the study, design and management of sustainable agroecosystems [8] (ain’t that a catchy definition). Agroecology is the next step beyond “organic”—it is ecologically sustainable, yet allows the wise use of pesticides and fertilizers. At this time, it appears to me that the neonicotinoid insecticides are a step forward in the transition from the nasty organochlorines, organophosphates, and carbamates toward more environmentally-friendly pest control products.

Other Pesticides

Several beekeepers tell me that their colonies experience serious mortality when farmers apply glyphosate herbicide (Roundup) in early July. This is odd, since the active ingredient is nearly nontoxic to bees. My guess is that the adjuvants (notably the “spreaders”) are the actual cause of mortality. Beekeepers need to bring such bee kills to the attention of the EPA, since EPA currently only looks at the toxicity of active ingredients, not the adjuvants [I stand corrected—Dr. Tom Steeger of the EPA explains that “If there are data indicating that the formulated product is more toxic than the active ingredient alone, then the Agency can and does call in data on the formulated product. EPA has required data on the formulated products of glyphosate and has data specific surfactants used in the formulations. These data have been used to develop mitigation measures (label language) to reduce effects on nontarget organisms”].

And how about the major pesticides found in hives? Those are the miticides applied by beekeepers themselves, which often form the toxic “base” upon which any agricultural chemicals are then stacked. You may have noted that neither Danny nor Tim apply any of these miticides to their hives, which may very well have something to do with why their colonies appear to be able to tolerate the agricultural pesticides so well.

Heads Up about a Recent Enforcement Action!

Western Farm Press, May 2, 2012: California pesticide dealers hit with $105,000 fine

• Two California pesticide dealers were penalized a total of $105,000 for knowingly selling a pesticide product [Comite] for a use not allowed by the label — controlling mites on [peach trees].

• DPR immediately directed removal of $1.1 million worth of peaches from the market.

I suggest that commercial beekeepers reread the above, but substitute “Taktic” for Comite, “bee hives” for peach trees, and “honey recall” for removal of peaches from the market. Think about what would happen if the DPR hits the manufacturers or distributors of Taktic with a serious fine because the distributors are knowingly selling it to beekeepers, or if a million dollars of honey was “removed from the market” due to illegal residues?

Think About It

I know that this report is going to rub some people wrong, and that opprobrium will probably be heaped upon me, but just think about it. The environmental consciousness of the country is at a high, and bees are in the spotlight. Do you not think that the pesticide companies are aware of this? These guys plan for the future, and they know that the future does not include the sorts of nasty poisons that we used to spray all over the landscape.

Read the patent applications and check the acquisitions for Bayer, Syngenta, BASF, Dow, and Monsanto. Their direction is toward the development of more environmentally-friendly pesticides—due to political pressure on the EPA to restrict or eliminate the use of the bad actors. Not one of these companies wants to be accused of being responsible for killing honey bees or butterflies, but they still want to sell product. So they are being forced by the market to come up with better products!

Work Together

Are pesticides still a problem for bees? Absolutely! How can we improve the situation? By taking up the offers of the pesticide companies to work with beekeepers (they are ready and willing), by supporting the EPA, and by filing “incident reports” so that the EPA has evidence of any problems caused by pesticides.

Educate your growers:

- Spray at dusk.

- Avoid overspray.

- If using systemics, avoid multiple treatments.

- Use untreated seed when possible.

- Practice Integrated Pest Management (IPM)—don’t spray unless necessary.

- Look for win-win situations that work for both the grower and the beekeeper!

If you keep bees in the states of Indiana, Minnesota, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, Montana, or Nebraska, be sure to register your apiary locations with Purdue’s excellent Driftwatch program (http://www.driftwatch.org/) which, in my opinion, beekeepers should press to implement in every state! Applicators voluntarily check the Driftwatch database for beekeeper locations prior to spraying, and then contact any potentially affected beekeepers. Danny Slabaugh told me how a couple of years ago an aerial applicator needed to spray bee-killing Lorsban on soybeans right next to one of his yards. The applicator called Danny, and agreed to spray in early morning, allowing Danny to smoke all the entrances to keep the bees inside. Win-win!

Report Incidents!

Dr. Tom Steeger of the EPA explains, “If beekeepers don’t report incidents, then EPA is blind to the potential effects which pesticides may be having under actual use conditions.” The preferred method is to get the cooperation of state agencies, so that they can take official samples for analysis. In this regard, diplomacy may help. Many state or county agencies are understaffed and overworked, and if you come on too stridently, they may simply dismiss you.

I’ve posted Dr. Steeger’s recommendations for filing incident reports at https://scientificbeekeeping.com/pesticide-incident-reporting/.

Unfortunately, in some states, the local agencies have decided that they are going to give growers free reign to spray whatever they want, with no consequences. This is in clear violation of the law (Figure 13).

Figure 14. Legal restrictions on a typical insecticide label. Misapplication is against the law! The AHPA is hoping to put pressure on states to uphold the law. Highlighting mine.

Final Conclusions

- To my surprise, in speaking with a number of knowledgeable beekeepers in the Corn Belt, I got the distinct impression that planting dust and corn insecticides in general were not serious issues for most beekeepers.

- Clearly, planting dust details need to be resolved in order to eliminate situations that result in serious bee kills, which can severely set back colonies and cost commercial beekeepers substantial lost income. In order to do so, the stakeholders (growers, beekeepers, the pesticide companies) and EPA need to cooperate in investigating the factors involved.

- Problems associated with those classes of pesticides previously thought to be “bee safe” (fungicides and herbicides) must be investigated, plus the adjuvants used in formulations, as well as the synergies involved when several pesticides are applied simultaneously.

- On the other hand, it appears that we are making progress with pesticides, and that bees can survive in agricultural areas. The most surprising thing to me was the degree of success at beekeeping enjoyed by my hosts, despite being surrounded by acreages of corn and soy. I understand that it is unfashionable to be optimistic about either beekeeping or the environment, but I’m just having a hard time buying the whole gloom and doom scenario!

- And the extinction of the honey bee? To paraphrase Mark Twain, it appears that the reports of the demise of the honey bee are greatly exaggerated. Bees and beekeepers are thriving in the Corn Belt, and I found no evidence that they are in imminent danger of going extinct!

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr. Tom Steeger, US EPA, for his helpful comments on the manuscript. He ended his comments saying that “I applaud efforts to get beekeepers to report beekill incidents and to foster a cooperative relationship with growers. I also am pleased to read that the off-label use of miticides is being discussed and aggressively discouraged.”

References

[1] http://www.avaaz.org/en/bayer_save_the_bees/

[2] Gibbs, M (2012) Bayer: Pesticide Profits or Bees? Forbes http://www.forbes.com/sites/markgibbs/2012/04/26/bayer-pesticide-profits-or-bees/

[4] http://www.intellicast.com/Local/Observation.aspx?location=USIN0624

[5] CATCH THE BUZZ. Corn Planting Drift is Killing Honey Bees. You Can Help. Here’s How. http://home.ezezine.com/1636/1636-2012.05.11.14.40.archive.html

[6] Pesticide program dialogue committee needs your help: beekeeper survey for pesticide-related bee kills. http://www.abfnet.org/

[7] Bee Kills in the Corn Belt: What’s GE Got to Do With It? http://readersupportednews.org/opinion2/271-38/11497-bee-kills-in-the-corn-belt-whats-ge-got-to-do-with-it

[8] De Schutter, O (2010) Report submitted by the Special Rapporteur on the right to food. http://www.srfood.org/images/stories/pdf/officialreports/20110308_a-hrc-16-49_agroecology_en.pdf This is a worthwhile report to the U.N. on the future of food production.

[9] van den Bosch, R (1978) The Pesticide Conspiracy. University of California Press. A great read about the “bad old days.”

(Apenet 2010) “Effects of coated maize seed on honey bees” http://www.reterurale.it/downloads/APENET_2010_Report_EN%206_11.pdf This is a good example of the sort of excellent and meticulous work that a coordinated group of Italian researchers are doing so solve bee mortality and pesticide issues.

Girolami, V, et al (2011) Fatal powdering of bees in flight with particulates of neonicotinoids seed coating and humidity implication. J. Appl. Entomol. 136(1-2): 17-26. Free download—I recommend. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1439-0418.2011.01648.x/pdf

Krupke CH, Gj Hunt, BD Eitzer, G Andino, K Given (2012) multiple routes of pesticide exposure for honey bees living near agricultural fields. PLoS ONE 7(1): e29268. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029268

Lodesani, M, et al (2009) Effects of coated maize seed on honey bees. http://www.cra-api.it/online/immagini/Apenet_2009_eng.pdf

Marzaro, M, et al (2011) Lethal aerial powdering of honey bees with neonicotinoids from fragments of maize seed coat. Bulletin of Insectology 64(1): 119-126.

Tapparo, A, et al (2012) Assessment of the environmental exposure of honeybees to particulate matter containing neonicotinoid insecticides coming from corn coated seeds. Environ. Sci. Technol 46 (5): 2592–2599.