Fat Bees – Part 1

Fat Bees – Part 1

Randy Oliver

ScientificBeekeeping.com

First Published in ABJ in August 2007

What if I told you that there was one amazing molecule in the honeybees’ bodies that allows them to store protein reserves, make royal jelly, promotes the longevity of queen and “winter” bees, is a part of their immune system, allows them to brood up in spring in the absence of pollen, and has an effect upon their foraging behavior? Surely you’d want to be familiar with such an important molecule!

Its name? Vitellogenin

This spring I was in the beeyard showing a class of kids a beautiful comb of very young brood. Every cell was glistening with “brood food.” I explained to the students the significance of that wonderous liquid, in that it was akin to the milk with which mammals nourish their young. Nearly all other animals on earth (with the exception of the nonsocial insects) either abandon their young to fare for themselves, or (in the case of birds) feed them the same food that the adults eat. Honeybees have the wondrous ability to feed their larvae with milklike secretions from their own bodies—royal jelly and “bee milk.”

Royal Jelly

These amazing products are actually a continuum of mixtures of glandular secretions, and of the nectar-rich contents of the honey sacks of nurse bees of the right age. Worker larvae receive “worker jelly” for the first two days, consisting of a white, lipid-rich secretion from the mandibular glands, and a clear, protein-rich secretion from the hypopharyngeal glands. After the first two days, the food for worker larvae shifts to “bee milk”–a mixture of “jelly” from the hypopharyngeal glands, and nectar from the honey sac. The food may also contain up to 5% pollen, but it appears to be an inadvertent “contaminant” from the nurses’ mouthparts or honey sacs. Worker jelly is low in sugar at first (with the sugar being mostly glucose), then increases in sugar content for older larvae (with the sugar type shifting to fructose).

Larvae floating in jelly. Similarly to mammals, honey bees feed their young a perfect food–a glandularly-secreted “milk.”

Queen larvae, on the other hand, are fed royal jelly continuously. This jelly consists of roughly equal amounts of secretions from both glands, has a higher sugar content, and different vitamin content than worker food. Surprisingly, queens are the default product of every fertilized egg! Only by reducing the amount of food fed, the type of food, and the size and orientation of the cell, can the colony suppress “normal” queen development, in order to produce nominally sterile workers.

Royal jelly is the most perfect food on earth—for queen bees. Queen larvae are fed lavishly, and float in a pool of creamy white jelly, from which they feed like Sumo wrestlers, gorging themselves to the excess needed to become the shapely beauties we prize (bee larvae do not defecate until their final moult, and thus do not foul their food). Queens are then fed royal jelly for the rest of their lives, by nurse bees in the brood nest. The queen must again eat amazing quantities—she lays nearly her body weight in eggs every day during peak colony buildup, which requires a prodigious amount of nutrition!

Pollen

So far I’ve only discussed the food requirements of larvae and queens. Adult worker bees also need to eat, and they are “born” hungry! As soon as they hatch, they head for the feed trough, first for a shot of sugar to give them energy. The brood combs are ringed by cells of open nectar or honey, readily available for the ravenous nurse bees, who are producing all the brood food to feed the larvae. Of course, everyone knows that you can’t raise kids on sugar alone, but that’s about all that nectar or honey provide. So our newly-hatched bee then seeks out cells of stored pollen next to the brood, and begins the process of building up her body protein level. She eats a little within the first several hours after emergence, really starts packing it in by two days, and tanks out around day five. At this point, her brood food glands and fat bodies are fully developed (provided that adequate pollen is available), and she can produce royal jelly. She will continue to consume pollen only if needed for further broodrearing, or to “fatten up” for winter. Once she becomes a forager, she will satisfy her protein requirements by soliciting protein-rich jelly from younger nurse bees (Crailsheim 1990).

The point that every beekeeper needs to understand is that the real nutrition for the colony comes from pollen. Specifically, a mixture of various and appropriate plant pollens, gathered by foragers, and carried back to the hive in the specialized pollen baskets on their hind legs. Pollen is synonymous with “bee food”—it provides the protein, lipids (fats), vitamins, sterols, minerals, and micronutrients that bees need for growth and health. Honeybee colonies require pollen in a big way—to the tune of 30-100 lbs a year! The stimulus for pollen foraging is largely the presence of brood pheremones produced by young larvae—hence, beekeepers who see pollen loads coming in at the entrance generally assume that the colony is queenright with brood present.

Nurse bees consuming pollen (yellow) and beebread (orange), in order to convert it into jelly.

Pollen foragers carry their pollen loads directly to the brood nest, and use their heads to pack it into cells adjacent to larvae. This pollen is generally consumed quickly by nurse bees. The dynamics of pollen storage and consumption produce the typical ring of pollen around the brood. Pollen that remains stored for longer periods may undergo lactic acid fermentation in the cell–this likely preserves it, much as similar fermentation does sauerkraut or yogurt. Cells of pollen may be covered with honey in fall to be used the next spring as the colony expands the broodnest prior to early pollen flows. This last point is a big one! Honeybees are tropical insects that need a warm environment and constant feeding (similar to humans). Similarly to humans, when they migrated from the tropics to more temperate climates, they “learned” to create dry homes (a cluster in a cavity) that they can heat to comfortable temperatures during winter, and to store food in their larders for lean times (i.e., any time that plants aren’t flowering).

Vitellogenin

O.K., in my roundabout way, I’m finally going to get to my point. Bees not only store pollen and honey in the combs, but they also store food reserves in their bodies. This is done mainly in the form of a compound called “vitellogenin.” vitellogenin is classed as a “glycolipoprotein,” meaning that is has properties of sugar (glyco, 2%), fat (lipo, 7%), and protein (91%) (Wheeler & Kawooya 2005). Vitellogenin is used by other animals as an egg yolk protein precurser, but bees have made it much more important in their physiology and behavior, using it additionally as a food storage reservoir in their bodies, to synthesize royal jelly, as an immune system component, as a “fountain of youth” to prolong queen and forager lifespan, as well as functioning as a hormone that affects future foraging behavior!

This is a great example of the conservatism of evolution. Just as the same genes that code for a fish’s fins also code for a dog’s paw, a human hand, or a bird or bat’s wing, bees have expanded the role of vitellogenin to perform multiple functions in their systems. They are able to do this because most of the bees in a colony are sterile females who rarely lay eggs. Therefore, they have the mechanism to produce this egg yolk precurser, but no use for it. So instead, they deposit it in fat bodies in the abdomen and head.

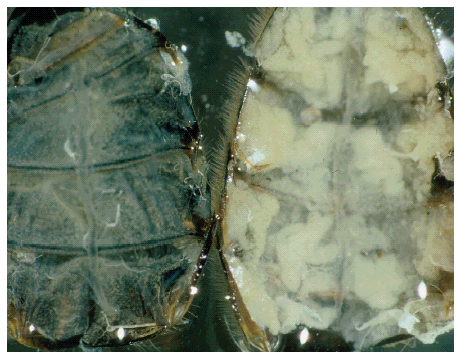

Fat bodies (white), reduced in a forager (left), fully developed in a “winter bee” (right). Photo credit (by permission): Keller, I P Fluri, A Imdorf (2005) Pollen nutrition and colony development in honey bees: Part 1. Bee World 86(1): 3-10.

Now, fat bodies aren’t just fat. Putnam & Stanley (2007) put it well: “In addition to its important roles as a storage depot, the fat body of insects functions as a key center of metabolism and biochemistry… fat bodies biosynthesize and accumulate not only lipid reserves, but also carbohydrates, amino acids, proteins and other metabolites. …[F]at bodies respond to physiological and biochemical needs in a number of ways, including very high rates of protein biosynthesis, formation and release of trehalose, release of lipids, detoxification of nitrogenous waste products, and biosynthesis of hormones… Many of the proteins that are crucial in the lives of insects are biosynthesized in fat bodies” (including vitellogenins).

Now here’s where Dr. Gro Amdam comes into the picture. While she was pursuing her thesis at the Norwegian University of Life Science in 2002, she wondered what all the vitellogenin synthesized by bees was doing. She found out that instead of being used for egg yolk protein, it was being fed to queens, larvae, and older workers (Amdam, et al 2003). “The insight that vitellogenin was important during the nest stage, and thus for worker division of labour, led Amdam to speculate that the protein could–directly or indirectly–affect the bees transition from nest tasks to foraging duties. ‘The age at onset of foraging is highly variable, but there was no good physiological model for explaining this variation. One possibility was that the probability of starting foraging was related to the level of the bees’ dynamic vitellogenin stores. This would ensure that vitellogenin-rich bees stayed in the nest as useful nurses of the brood and other bees, whereas vitellogenin-exhausted bees became foragers’” (Anon 2007).

In later research Amdam demonstrated that suppression of vitellogenin leads to high titers of juvenile hormone–a systemic hormone associated with insect development, and honeybee foraging activity. Unlike in other insects, vitellogenin and juvenile hormone now work antagonistically in the honeybee to regulate their development and behavior (Nelson, et al. 2007).

Furthermore, Dr. Amdam showed that vitellogenin scavenged free radicals from the bees’ systems, thereby allowing queens and winter bees to live longer, by suppressing oxidative stress damage (Seehuus, et al. 2006). Vitellogenin is indeed the “Fountain of Youth for the honeybee! Maybe the health claims for royal jelly have merit—if you were to eat enough of it. By implication, since juvenile hormone levels spike in stressed bees, vitellogenin may have a role to play in fighting stress (Lin & Huang 2004).

Schmickl and Crailsheim (2004) have published a most informative review of nutrient flow dynamics in honey bee colonies—this is must reading for any serious beekeeper! It’s a free download, and I’ve included the URL in the references. To summarize their comprehensive paper, protein from pollen, and sugars from nectar, are in dynamic states of movement in the colony based upon the availability of the raw materials from foraging, and the nutrient requirements of the queen, larvae, nurses, foragers, and drones. There are complex feedback and behavioral mechanisms to ensure that food reserves are shared and distributed optimally in both good times and bad.

Incoming nectar is quickly distributed within the hive among all age groups of bees, and to the larvae. But it’s the dynamics of protein transfer within the colony that are really important to understand! Especially the degree to which nurse bees are continuously feeding the foragers. In experiments, up to 25% of radioactively tagged amino acids fed to nurse bees were transferred to foragers overnight! Nurse bees not only feed brood, but also are continuously feeding protein to the foragers.

Pollen dearth

Pollen foraging by those foragers is stimulated not only by brood pheremones, but also by the inventory of pollen stores, and the amount of jelly in the shared food fed by nurse bees to the foragers. The quality of the jelly is dependent upon the vitellogenin levels of those nurses. Even just a few days of rain results in an almost total loss of pollen stores, forcing the nurse bees to dig into their vitellogenin reserves. When protein levels drop, nurse bees neglect young larvae, and preferentially feed those close to being capped. When protein levels drop lower, nurses cannibalize eggs and middle aged larvae. The protein in this cannibalized brood is recycled back into jelly. Nurses will also perform early capping of larvae—resulting in low body weight bees emerging later.

When a colony goes into protein deficit, the nurses cut back on the amount of jelly fed to larvae. Note how little jelly these larvae have been given. Pollen-starved nurses may also consume newly-laid eggs, and eventually larvae.

What’s happening is that the honeybee has figured out ways to keep most of the precious protein stores within the hive, and since vitellogenin is necessary for immune function (Amdam 2005a), the colony delegates the risky task of foraging to the oldest bees, who have depleted their vitellogenin levels. Indeed, if older bees are forced to revert to nurse behavior, and build up their protein reserves, their immune level also increases again! Vandam points out that “A functional immune system is apparently costly in social insects,” so don’t waste it on the foragers. “When bees switch from the hive bee to the forager stage, their cellular defence machinery is down-regulated by a dramatic reduction in the number of functioning haemocytes (immunocytes)” (Amdam, et al. 2004a).

Fat bees and wintering

So the European honeybee, in adapting for the long winters of temperate climates, has figured out ways to store energy in the form of honey for the winter, and protein in the form of vitellogenin. This allowed the species to maintain a large social population year round, despite the vagaries of nectar and pollen flows. Amdam (2003) states: “the vitellogenin-to-jelly invention…made possible the establishment of a very simple and flexible ambient condition-driven mechanism for transforming a nurse bee into a bee with large enough protein and lipid stores to survive several months on honey only.” When broodrearing is curtailed in fall, the emerging workers tank up on pollen, and since they have no brood to feed, they store all that good food in their bodies, thus preparing themselves for a long life through the winter. These well-nourished, long-lived bees have been called “fat” bees (Sommerville 2005; Mussen 2007). Fat bees are chock-full of vitellogenin. Understanding the concept of fat bees is key to colony health, successful wintering, spring buildup, and honey production.

Indeed, one of the big differences between African and European bees is the degree of fatness. Back to Amdam again (2005b): “Our data indicate that European workers have a higher set-point concentration for vitellogenin compared to their African origin. Considered together with available life history information and physiological data, the results lend support to the view that “winter bees”, a longlived honey bee worker caste that survives winter in temperate regions, evolved through an increase in the worker bees’ capacity for vitellogenin accumulation.” Thus the African bees’ strategy of absconding and searching for new food resources, rather than hunkering down and waiting it out.

Foraging and swarming

Think that’s all there is to vitellogenin? Dr. Amdam got together with California’s Dr. Rob Page (Nelson, et al. 2007), who had previously developed a pollen-collecting line of bees. Page had found that bees genetically biased to collect pollen were characterized by high levels of vitellogenin. Together the researchers discovered that the vitellogenin titer developed by a worker bee in its first four days after emergence, affected its subsequent age to begin foraging, and whether it preferentially foraged for nectar or pollen! If young workers are short on food their first days of life, they tend to begin foraging precociously, and preferentially for nectar. If they are moderately fed, they forage at normal age, again preferentially for nectar. However, if they are abundantly fed immediately after emergence, their vitellogenin titer is high, and they begin foraging later in life, preferentially collect pollen, and have a longer lifespan. This scenario certainly makes sense—a starving colony would want skip raising brood, and send out foragers to gather as much nectar as they could. A fat colony would want to rear brood and build protein reserves in order to swarm.

The high proportion of returning pollen foragers indicate that this colony is probably rearing brood.

It’s likely that vitellogenin levels are also involved in swarming behavior. Zeng, et al. (2005) found juvenile hormone levels to drop preswarming—implying that vitellogenin levels rise (since the two are antagonistic). This would be expected, since a swarm would want to pack along as much vitellogenin as possible, and would be unlikely to leave home without it. High vitellogenin levels would also make swarm bees longer lived and healthier. It’ll be interesting to find out how vitellogenin titers relate to swarming behavior. This surprising effect of a storage protein affecting consequent bee behavior again raises the subject of epigenetics, which I discussed in Choosing Your Troops (Watters 2006). Could nutritional or stress events affect subsequent behavior or immune function in a colony for an extended time?

Colonies raise swarm cells only when nutrition is optimal. Should the colony go short on pollen, it will abort swarm buildup, and tear down the swarm cells.

Vitellogenin and varroa

Aren’t you wondering when I’m going to mention the varroa mite? Well, Dr. Amdam (2004b) thought of that too! “Compared with noninfested workers, adult bees infested as pupae do not fully develop physiological features typical of long-lived wintering bees. Management procedures designed to kill V. destructor in late autumn may thus fail to prevent losses of colonies because many of the adult bees are no longer able to survive until spring. Beekeepers in temperate climates should therefore combine late autumn management strategies with treatment protocols that keep the mite population at low levels before and during the period when the winter bees emerge.” Hence, the critical August 15th date to get varroa levels down. Mite-hammered bees can’t put on enough vitelligenin to make it through the winter, and then rear the first round(s) of brood in early spring.

When a pupa is parasitized by varroa, it will never become the bee that it could have.

Seasonal protein levels

Now we get to a researcher who is underservedly little-known in the U.S.—Dr. Graham Kleinschmidt from Australia. Kleinschmidt, often in partnership with AC Kondos, extensively studied honeybee body protein levels (they didn’t mention the word “vitellogenin,” but that’s what a protein assay would pick up). They found that protein levels varied seasonally. “The level of body protein in adult bees ranges varied between 21% and 67% in direct relationship to the quantity and compostion of available pollen protein and work load imposed by reproduction and honey collection” (Kleinschmidt and Kondos 1977). When colonies are working a heavy honey flow, their body protein level drops, even if limited pollen is available! If they suffered a pollen dearth before the flow, their protein levels can drop severely, shortening their lives, and restricting their ability to rear brood. Colony recovery time depends upon how low the bees’ protein level got, how much brood they have, and the availability of pollen, but may take up to 12 weeks! If protein levels didn’t get below 40%, recovery can occur in two weeks to a month.

In summary, protein is precious to the honeybee colony, and its sole natural source is a mixture of plant pollens. Bees store reserves of protein in the bodies of house bees in the form of vitellogenin, and conserve those reserves zealously, by recovering them before house bees graduate to become field bees. Field bees thus give up the life-extending and immunicological benefits of vitellogenin. Protein is transferred within the colony from bee to bee by the sharing of vitellogenin produced by nurse bees. Vitellogenin levels affect the foraging behavior of field bees. Nurse bees, queens, and winter bees are long-lived and more stress and disease resistant due to their high vitellogenin titers. Successful wintering is dependent upon the last rounds of bees emerging in the late summer/fall having adequate pollen available in the broodnest.

Now, I’ve offered you enough scientific knowledge to begin to understanding the critical role that vitellogenin plays in colony life. Lots to digest, huh? This subject may take a second read! So how can you apply this knowledge to have healthier bees, better resistance to mite damage, better wintering, stronger colonies in almond (or other) pollination, and bees that can produce the largest honey crops? Sorry, I’m out of space—I’ll be back next month to talk about supplemental feeding.

References

Amdam, GV, K Norberg, A Hagen, SW Omholt (2003) Social exploitation of vitellogenin. PNAS 100(4): 1799-1802.

Amdam, GV, et al. (2004a) Hormonal control of the yolk precursor vitellogenin regulates immune function and longevity in honeybees. Exp Gerontol.39(5):767-73.

Amdam, GV, K Hartfelder, K Norberg, A Hagen, SW Omholt (2004b) Altered Physiology in Worker Honey Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Infested with the Mite Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae): A Factor in Colony Loss During Overwintering? Journal of Economic Entomology 97(3): 741-747.

Amdam GV, et al. (2005) ; Social reversal of immunosenescence in honey bee workers Experimental Gerontology 40(12): 939-947

Amdam, GV, K Norberg, SW Ohmolt (2005b) Higher vitellogenin concentrations in honey bee workers may be an adaptation to life in temperate climates. Insects Sociaux 52(4)

Anon. 2007 Genetic links illuminate bee social life. Australian Life Scientist 13/03/200

Keller, I, P Fluri, A Imdorf (2005) Pollen nutrition and colony development in honey bees. Bee World 86(1): 3-10.

Kleinschmidt and Kondos (1977) The effect of dietary protein on colony performance. Proc. 26th Int. Cong. Apic., Adelaide (Apimondia).

Lin, H., C. Dusset & Z.Y. Huang. 2004. Short-term changes in juvenile hormone titres in honey bee workers due to stress. Apidologie 35: 319-328.

Mussen, Eric (2007) FOOD for thought. Apicultural Newsletter March/April 2007. Dr. Mussen’s newsletters are some of the best references on issues related to almond pollination. http://entomology.ucdavis.edu/faculty/mussen/news.cfm

Nelson, CM, KE Ihle, MK Fondrk, RE Page Jr., GV Amdam (2007) The Gene vitellogenin Has Multiple Coordinating Effects on Social Organization. Public Library of Science https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.0050062

Putnam, SM & DW Stanley (2007) Entomology 801 http://entomology.unl.edu/ent801/fat.html

Schmickl, T & K Crailsheim (2004) Inner nest homeostasis in a changing environment with special emphasis on honey bee brood nursing and pollen supply. Apidologie 35: 249-263. https://www.apidologie.org/articles/apido/abs/2004/03/M4009/M4009.html

Seehuus, SC, et al. (2006) Reproductive protein protects functionally sterile honey bee workers from oxidative stress. PNAS 103(4): 962-967.

Somerville, Doug (2005) Fat Bees Skinny Bees, A manual on honey bee nutrition for beekeepers. Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation, Australia. Available on the Web at https://www.agrifutures.com.au/wp-content/uploads/publications/05-054.pdf https://rirdc.infoservices.com.au/downloads/05-054

Watters, Ethan. 2006. DNA Is Not Destiny. Discover Nov. 2006, pp. 32-37, 75.

Wheeler, DE & JK Kawooya (2005) Purification and characterization of honey bee vitellogenin. Archives of Insect Biochemistry and Physiology 14 (4): 253-267.

Zeng, Z, Z Huang, Y Qin, H Pang (2005) Hemolymph Juvenile Hormone Titers in Worker Honey Bees under Normal and Preswarming Conditions Journal of Economic Entomology 98(2): 274-278.