California Dreaming vs. California Reality: The Status of Almond Pollination for 2007 – Part 1

California Dreamin’ vs. California Reality:

The Status of Almond Pollination for 2007

Part 1

By Randy Oliver with Keith Jarrett

© Randy Oliver 2007

ScientificBeekeeping.com

First Published in ABJ in October 2006

Photos to be added

Last year California relived the Gold Rush of 1849. But this time the rush was not for the precious metal, but rather to high pollination rents in the almond groves. In both “Rushes” the elements of rumor, speculation, greed, and financial disaster were much the same. There has been much discussion in the beekeeping community about what happened. Unfortunately, this coming season is shaping up to be yet another crapshoot, again fueled by rumor, rather than hard facts. In this article I hope to give both the beekeeping and almond growing industries a summary of the California view of the realities of the situation.

We will begin with an introduction of the major players and terms, then discuss the important variables in the price equation, summarize the perspectives of the major players, give an outlook of the future, and offer advice for pollinators and growers.

I want to thank my friend and fellow beekeeper for his help with this article. Keith is a very sharp and progressive beekeeper who does something that many of us fail at: HE MAKES A LOT OF MONEY FROM BEEKEEPING! That impresses the hell out of me, and gives his input great credence.

The Almond Crop

First, let’s introduce the main player–the almond. By the way, if you grow ’em, you pronounce their name as “amonds” (rhymes with salmon–one needs to beat the “L” out of ’em to harvest ’em). The almond is closely related to the peach, but instead of eating the fleshy outer covering, we discard it as a “hull” and eat the “pit.” Almond trees require a Mediterranean climate, which limits the regions in the world where they can be grown. California produces 80% of the world’s supply; the rest is grown in Greece, Spain, Iran, and other Mediterranean countries. Expansion of the other producers is limited by lack of water and good soil, thereby granting California growers a valuable “global exclusivity.” Almonds are California’s sixth leading agricultural product and its top agricultural export.

In 2003, due to worldwide demand and aggressive marketing, almond prices climbed. Growers responded by placing orders for new trees—nearly 30,000 acres were planted in 2005! The wild planting spree has continued each year as the price paid for nuts skyrocketed to a peak in 2005. Farmers are ripping cotton and replacing it with almonds. Vast new orchards are a common sight in the Central Valley. When we dropped off our bees in almonds this Spring, we saw thousands of rows of tiny grafted almond twigs in white protective sleeves, stretching clear to the horizon! New orchards, densely planted, with state-of-the-art drip irrigation, and new varietal plantings on good soils, can yield astounding crops of up to 4000 pounds of nut meats per acre in a few years, and prices are holding up for the time being. There are currently about 620,000 acres of almonds planted in California, of which about 11% are non-bearing.

“As late as the 1950s, early-blooming NePlus, mid-blooming Nonpareil and late-blooming Mission were popular plantings. Such a variety mix would be fine for apples, which require only a 10 percent set of flowers for a satisfactory crop, but the arrangement doesn’t work for almonds where 50 percent set of flowers is needed for maximum yields – depending on the number of flowers. Considering that an almond flower is only receptive to pollination for a few days, relatively low yields on early plantings were the norm” https://www.beesource.com/threads/bees-coming-up-short-in-almonds.194934/page-3#post-84875 . The new dense plantings are a wonder to behold in bloom—an unbelievable solid mass of white/pink flowers. These plantings require serious bee pollination to set the record crops the growers seek.

Almond trees have an unusually early bloom period normally beginning February 10th. The commercial varieties are largely self incompatible, which means that two or more varieties need to be planted in an orchard to ensure cross pollination. Come February, nearly a thousand square miles of California becomes a pink and white artificial forest of almond bloom. Since almonds are now grown as a monocrop with nary a flowering weed in sight, there are few natural pollinators available at that time of the year. This is when honeybees enter the picture, since they are the only cost-effective method at this time to transfer enough pollen from tree to tree to set the maximum crop. The pollination of California’s almonds is the largest annual managed pollination event in the world, with about one million hives (nearly half of all beehives in the USA) being trucked in from out of state in February to the almond groves (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Almond).

History of Pollination Prices and what happened last year

Back in the “good old days,” beekeepers would ask permission of almond growers to place their bees in the orchard during bloom, since the colonies build up well on almond pollen and nectar, and back then there were abundant flowering weeds in and around the orchards. As almond plantings increased, some beekeepers had the audacity to ask the growers for a 25¢ per colony rental fee! The growers screamed bloody murder, but begrudgingly paid. By the time I started pollinating in the early 1980’s, the price had risen to about $12 per colony, then climbed each year at a steady rate; by 2004 bloom it had reached $45 for strong colonies. Then in late 2004 (prior to the 2005 bloom) Varroa mites and viruses devastated the beekeeping industry at the same time that the almond acreage started to expand—the price for bees nearly doubled to $80. Last season (2006 bloom) almond nut prices were way up, and growers got worried that they would not get enough bees. So they started bidding against each other to ensure that if there was a shortage, their orchard would not go without. This is an important point that the growers would do well to remember. The high rental fees totally caught the beekeepers by surprise–they didn’t bid up the price, the growers did. It was a classic case of supply and demand, the “demand” being growers salivating over making a killing due to high nut prices (dependent, of course, upon having adequate bees), and “supply” being beekeepers struggling to keep their colonies alive.

Beekeepers across the country got wind of the high rents being offered on the West Coast, and in a fit of greed matching that of the growers, pried nearly every box that appeared to contain bees off the ground and trucked them to California, often without benefit of a waiting contract. The results were a debacle, as detailed in ABJ last April. In a nutshell, offered prices started out high (in the $150 range), until growers realized that there appeared to be a glut of bees at hand. In reality, there was a glut of bee boxes! Growers then started demanding that beekeepers prove the strength of their colonies in order to receive high rental fees, and Midwestern beekeepers felt hoodwinked that growers wouldn’t accept their weaker colonies; some didn’t even clear enough profit to pay for diesel fuel for the trip home! As the February 10th blooming date approached, desperate beekeepers cut each others’ throats in a price tumble down to the $80 range for the last few colonies placed. Contracts were cancelled, beekeepers played “musical chairs” with weak colonies as growers rejected them after placement in their orchards. Worse yet, strong, healthy colonies went unplaced at all! It was an ugly situation all around! The end result was that the growers were upset, the beekeepers were upset, and there was a great loss of trust between all parties.

So where do we stand going into the 2007 season? Here are some facts: new acreage coming into production will require more colonies than last year. There are about 580,000 acres requiring bees–at a rate of something over two colonies per acre average, growers will be asking for over 1.3 million colonies! There are something in the ballpark of 2.4 million colonies in the entire U.S., including those owned by hobbyists, and those that are not readily available to be moved. You do the math.

So the big question is: What is the 2007 price for pollination going to be? In order to get a good perspective, I interviewed most of the major players (beekeepers and brokers representing nearly 25% of all colonies going into pollination), small to mid-sized beekeepers, individual growers and packers, the Almond Board, pollination researchers, and drew upon our own experiences as almond pollinators for many years. Due to hard feelings in the industry last year, many of the persons we interviewed preferred not to be quoted by name.

I will begin the discussion with the topic of “grading.”

Grading of colony strength

For many years, almond growers and beekeepers had a comfortable working relationship. Beekeepers liked to build their bees up in almonds, and growers paid a reasonable fee to make it worthwhile for the beekeepers to haul them in and out. Bees were typically brought in “field run,” with extra colonies usually brought in to cover any deadouts or weak ones. As long as the growers saw bees flying in and out of the boxes, and made a crop, everyone was happy.

Hard as it is to imagine, some unscrupulous beekeepers, capitalizing on the growers’ fear of bees, would occasionally bring in deadouts containing honey along with their live colonies. Of course, the deadouts would be robbed by other colonies, giving the appearance of strength due to the robbing traffic at the entrance. In actuality, the robbing diverted bees away from pollinating. Growers got wise to this trick, and started to look inside the boxes, either privately, or with the beekeeper, or by having an independent party (such as the County Ag Commissioner) do an inspection.

As the price paid for colony rent climbed, the growers naturally wanted to make sure that they were getting what they paid for. Thus was born the concept of “frame strength.” The concept is similar to requiring a “net weight” on a box of cornflakes. If you’re paying for a pound of cornflakes in a box, you’d be disappointed if you only got a handful. If you’re paying for a strong colony, you would specify a six- or eight-frame strength. So for years the typical contract would call for a six- or eight-frame average, with a four-frame minimum strength, again with extra colonies brought in to make up any found to be too weak.

As pollination rents approached the $50 level, we saw more and more growers requiring some sort of “truth checking” of colony strength. Often this was no more than a walkthrough of the pollinating colonies in the orchard during early bloom, with the beekeeper offering to pop lids where there was any question. California beekeepers tended to return to the same orchards year after year, and developed friendly working relationships with the growers. Any colonies in question were eliminated from the “count,” and replacement colonies brought in if needed.

Last year, some Midwestern beekeepers new to California were caught by surprise when they found that their colonies didn’t “make grade.” Some had to be combined two or three to one to make an acceptable unit. There was even talk of “California grading” being unfair. We Californians have long been accustomed to a standardized criterion: a “frame” of bees is the equivalent of one deep Langstroth frame 70% covered with bees at a temperature above 60°F (so that the cluster has broken). That’s not an inch of bees along the top bar, but a full frame covered top to bottom. When colonies are inspected in middle of the day, much of field force is out, and inspectors should make allowance for that. Colonies generally grow by several frames during the almond bloom. Growers want inspection at 10% bloom; beekeepers want inspection as late as possible, to allow the colonies to grow.

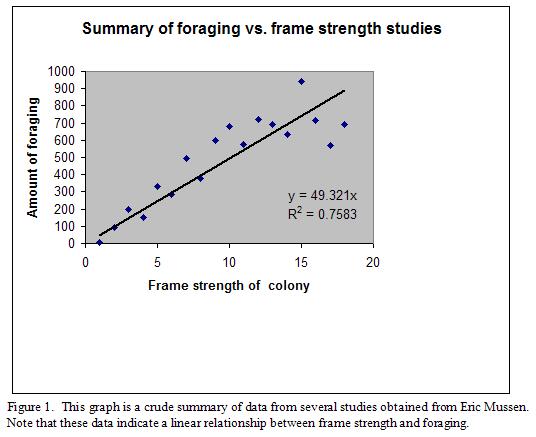

So why is grading important? Simply put, stronger colonies do more pollination. According to two studies, during spring pollination, an 8-frame colony can send out 7 to 10 times as many workers as a 4-frame colony. I wondered about even stronger colonies, and obtained data from Dr. Eric Mussen, the University of California Extension Apiculturist, who is very helpful and knowledgeable on all beekeeping issues facing California. He forwarded me several sets of data correlating frame strength with foraging activity measured by either forager counts or pollen collected. To summarize, I crudely averaged all the data sets and plotted out the relationship (Figure 1). These data gave a somewhat different picture of a more linear relationship between frame strength and foraging. That is, these data indicate that compared to a 4-frame colony, an 8-framer would be twice as valuable, a 12-framer would be three times as valuable, and a 16-framer four times as valuable. The key factor appears to be the amount of brood present to feed. The more brood, the more pollen foraging.

So what does this mean to the beekeeper and grower? From my take of the data, a grower would get equivalent pollination from one 12-frame colony as three 4-frame colonies, and should pay the beekeeper accordingly. So if the standard 8-frame colony goes for $150, a 4-framer would be worth $75 to the grower, and a 12-framer would be worth $225! I suggest that the Almond Board might find that it would be money well spent to finance further research along this avenue.

O.K. Now that I’ve established why grading is important, who does the grading? There’s nothing wrong with the beekeeper and grower walking the orchard together. Alternately, the grower can request his County ag commissioner to perform an independent grading, although due to budget cuts, some counties are no longer doing inspections, and others may be overwhelmed by requests at start of bloom. Finally, some growers are more comfortable paying for an independent inspection by a private party or bee broker.

This is an important point to be learned by new pollinators– grading of colony strength is largely a trust issue. Beekeepers who have a long-term relationship with a grower are trusted to provide strong colonies year after year. John Miller (Newcastle, CA, and Gackle, SD), with over 10,000 colonies says: “Almond guys who lack relationships/trust with beeguys will probably rely on graders/inspectors more in the future.” He takes care of his own inspections: “We place the bees, and immediately go through them; removing duds, and substandard hives. We calculate to deliver extra, without question. We promptly report the count and the condition of the hives. Growers see empty spots on pallets, but can confirm the counts any day, any time.” Lyle Johnson (Madera, CA; the largest broker, bringing in well over 50,000 colonies) is proud to put his name on all the colonies he brings in, and has a crew of nine that inspect them at every step of the way.

From our interviews, we found that most growers were asking for some sort of colony strength guarantee, and many required some sort of inspection. Some growers are still accepting “field run’ bees at a discount. Most learned their lesson last year and aren’t willing to take the risk of finding that substrength bees have been delivered two days before bloom.

Some beekeepers sort their bees, and send the best to a graded high-paying contract, and the rest elsewhere. This takes us to the subject of…

Bee Brokers

The most recognized bee broker is Joe Traynor in Bakersfield. I gotta tell you, from my interviews with the important players, there is no one in California beekeeping more beloved or respected than Joe Traynor. His reputation for good information and honesty is beyond reproach. Let me quote you two unsolicited accolades: John Miller said “Joe Traynor holds the price, and performance umbrella for the industry in these troubled times, and he is damned well worth it!” Lyle Johnson says: “Joe Traynor is the engine that pulls the train.”

Joe has tirelessly educated almond growers about how to profitably grow almonds, and educated beekeepers how to provide strong colonies (just Google his name, or go to Beesource.com). He was the first to sound the warning about the impending shortages of bees for the huge almond acreage coming into production. He also sticks his neck out each year by committing to a price far in advance of the season—in June of the previous year! This benchmark price is referred to by all California beekeepers, and has cost Joe clients when it turned out to be above or below the market eight months later.

A beekeeper does not need a broker. Many California and out-of-state beekeepers contract directly with the grower, by word of mouth, advertisements in local papers, or by posting to the Almond Board website (www.almondboard.com/applications/polliinationdir/PollinationList.cfm). However, many experienced large and small beekeepers do use a broker’s services for some or all of their colonies.

It appears to me that there are four levels of brokerage:

Level one: the buddy who knows of a grower looking for bees, and puts you together as a friendly courtesy for a dollar or two per colony fee for his time.

Level two: brokers such as Charlene Carroll and Linda Hicken (www.beepollination.com) who have been in business since 1978, and place tens of thousands of colonies a year. Their fee was only $2 per colony until last year, when they raised it to $3. Their website is very informative, and details their services.

Level three: Brokers who provide formal colony grading inspections, paid for by the grower, who often get higher prices for beekeepers with premium colonies (see http://www.pollinator.com/Pollination_Beekeepers/polbrokers.htm). Examples would be Joe Traynor (Bakersfield area), Mike Rosso (North Valley), and Denise Qualls (Merced Co.—510-885-1014).

Level four: Scalpers who will take you for as much as they can. These can be other beekeepers!

I have found the brokers to be extremely knowledgeable and helpful. Services they provide to the beekeeper include:

Finding a grower appropriate for your area and the number of colonies you have available, setting the number and strength of colonies in each orchard, and type of loading (forklift , boom, hand, mule train).

Writing a good contract to protect both the beekeeper and grower. Act a beekeeper/grower liaison.

Setting up appropriate drops that have access, reasonable numbers, and won’t be underwater when it rains. Also, generating maps to the above.

Meet with the beekeeper in the orchard to locate drops.

Help beekeepers with State and County regulations, and with problems collecting payment.

Some brokers bill the grower and then pay the beekeeper, others have you bill the grower directly.

CAN USUALLY COVER YOU IF YOU COME UP SHORT ON BEES! This is a big plus for going with a broker.

Pay grading crews and resolve grading issues.

Work 24/7 for a long time.

Joe Traynor also donates $1 of his fee per colony to the CSBA research fund (in 2006, he donated $2/colony–$84,000 in all!)

Larger beekeeping outfits typically deal directly with the grower, yet even the biggest outfits may contract through a broker if the broker offers an exceptionally good orchard at a fair price–e.g., an orchard with graveled roads, large drops, and isolated from other beekeepers is especially attractive to the big boys. If 2007 will be your first time pollinating in California, you may wish to consider the services of a broker.

The 2007 Price—Important Factors

The 2007 price paid for pollination will be solely a function of the market forces of supply and demand. This industry cries for stability, but don’t count on it, with whipsaw wholesale pricing of almond nuts, feckless planting of trees, and a tenuous supply of honeybee colonies suffering from the Varroa mite. I’ve already mentioned that the overall number of strong colonies the almond industry will require in 2007 is about a 1.3 million. There are about a half million resident in California, with some unknown percentage available for pollination. There is likely an adequate supply in the rest of the U.S.—probably another two million colonies of various strengths. The question is, what price will be required to motivate those beekeepers to move about a million of them into California?

Bob Harrison last year referred to the setting of almond pollination prices as a “high stakes poker game.” I’d have to concur. So let me introduce to you some of the players, and the “hole cards”—the demand by the growers for bees, honeybee colony health, the vagaries of the weather, the wholesale price of honey, other sources of pollinators, and transportation issues—diesel cost and pest inspections at the border. I will then allow the players air their perspectives of the situation, and tell you how the game is shaping up.

Demand

There will be more bees required this year than last—how many more is a question. Statistics for plantings are based upon voluntary return of questionnaires, so there is considerable room for interpretation. Enthusiastic beekeepers hoping for high prices have cited a figure of perhaps 90,000 additional. A perhaps more sober analyst gave me a number in the range of 20-30,000 colonies, based upon the facts that there are about 34,000 acres of “third leaf” trees requiring about a colony per acre, and 32,000 acres of 4th leaf trees which took one colony last year, but will now take two, minus a nearly equal acreage of old trees being ripped out.

The industry overall is shifting from bearing acres of older trees that don’t require very many colonies, to dense plantings that do. Joe Traynor says :

“We’ve had a state-wide test plot in many recent years: [we got] bumper statewide crops even though many orchards had sub-standard bees …. If you look at an almond orchard in bloom and write down how many times an individual flower is visited I think most growers would agree to use less bees. I don’t think any grower should use more than 2 colonies/acre, even if they’re shooting for 3000+ lbs/acre yield… When I try to talk growers into using less, they say ‘I know I use too many bees most years, but I want them for that one year when the weather is bad, pollination is marginal, the crop is light state-wide and almond prices go through the roof as a result.’ I’ve heard this argument many, many many times and its virtually impossible to argue against.”

There are years in the North Valley when it rains nearly every day, and the entire year’s crop appears to be set by the bees in a few hours. Many growers just don’t want to gamble, especially if the price of nuts promises to be high. On the other hand, many growers with a history of good set are adjusting from 2.5 to 2.3 colonies per acre. The greater the price of nuts, the greater the demand for bees, due to the “economic threshold for inputs strategy,” meaning that it’s worthwhile to pay for more bees if the potential additional nut income due to greater set will cover the additional cost for the bees. In future years, we can realistically expect the price for nuts to drop, meaning that growers will start pinching their pollination pennies.

So the “Demand” card looks to be up by some number of colonies.

Mites and colony health

Last year many beekeepers were caught by surprise when varroa mites evolved resistance to the chemicals Fluvalinate and Coumaphos, and viruses ran rampant in their colonies. At the California Queen Breeders meeting in October, almost no one in the room had any idea how many colonies he would have alive at almond bloom time in three months! This year the beekeepers I’ve interviewed are much more confident. Most are using some combination of mite control agents and being proactive. The advice from successful beekeepers is that regular monitoring of mite levels is critical. If you wait until you are seeing mites on your bees, you’re starting too late!

Eric Mussen points out that you should not forget to deal with tracheal mite and Nosema disease if necessary, since he’s seeing a fair share of colonies damaged by each. If colonies are stressed by mites and disease in Fall, your Fall colony count may have little relationship to the number of strong colonies you’ll have in February! Indeed, many mite-stressed colonies simply collapse in the orchard the first week of bloom.

Most successful beekeepers in pollination feed their colonies with syrup and pollen supplement to boost colony strength in late Summer. If you want “big bees” in February, you need to go into Winter with a large cluster of well-fed young bees free of disease (for great info, search Eric Mussen’s web pages (Broken Link!) http://entomology.ucdavis.edu/faculty/mussen/news_index1.html).

The “Mites and Colony Health” card looks to be better than last year with regard to mites and disease, but there are some recent reports that some Midwestern operations do not have mites under control.

The Weather

The weather affects both beekeepers and almond growers. For the growers, the weather before and during bloom affects timing and duration of bloom, overlapping of bloom of pollinizing varieties, overall nut set (Broken Link!) (www.beesource.com/pov/traynor/agnewsmar1804.htm), amount of honeybee flight hours, freezing or hail damage to the blossoms and early nuts, fungus damage to the trees during wet Springs, trees being uprooted by winds, and the amount of irrigation required. The Valley can be cold, wet, and foggy during bloom, and only the strongest and cold adapted colonies may fly. For this reason, many growers stock bees especially heavily as insurance, sometimes at the rate of three or four colonies per acre! As you might imagine, at that stocking rate, the bees compete and don’t build up well.

Beekeepers are also affected by the weather during almond bloom. Storms in late January and early February can restrict access to the orchards. Once the bees are in, orchards can be flooded, drowning or washing away hives. February daytime temperatures in the Valley often hover right on the edge of bee flight (about 55°F), or they may soar into the 70’s. Depending on the weather, colonies may either starve or plug out with bitter almond honey. This year I had an orchard that the hives were trapped in for a month after bloom due to muddy conditions.

Midwestern beekeepers are also at the mercy of Winter weather. Many have taken to overwintering in potato cellars in Idaho, then moving directly to California. It’s too early to predict the Winter weather, of course.

Later in the year, beekeepers in some areas were strongly affected by the weather. According to the National Honey Report of August 10, the first half of 2006 was the driest on record in parts of South Dakota. The severe drought and heat in the Midwest caused entire yards of bees to abscond, and some were killed outright by 120°F temperatures. Some beekeepers lost half their bees. Many colonies in the southern parts of the Dakotas didn’t make honey and will be in poor condition going into Winter. Beekeepers intent on almond pollination tried to move to wetter areas, but (in the words of Richard Adee–the largest beekeeper in the U.S.) “The drought was just too big to move out of.” Reports from large Midwestern beekeepers (hoping for high prices) are that the Midwest may be down 100,000 colonies!

There were record high temperatures in California in July. Reports from beekeepers are that late splits made for increase were fried by the heat. As of August, California has dried up, and beekeepers are starting feeding early in some areas.

The “Weather” card hit the Midwest hard—100,000 colonies down may be hyperbole, but it’s not pretty. California splits suffered. Costs to feed bees will be up. No telling what Winter holds in store.

The Honey Market

The weather also affects the honey crop. The Midwest baked this summer, and the crop looks to be short. Drought and a major typhoon have affected China’s sugar production, and they are using honey in its place. Both these issues, plus antidumping regulations will drive up the price of honey. When the price of honey goes up, it becomes less attractive for faraway beekeepers to haul bees to California. With fuel costs up, they can make more money staying home, or going to Texas, to put on a honey crop. (I find it fascinating how a typhoon in China can affect whether a Florida beekeeper brings his hives to California!) Midwestern beekeepers must decide if it’s more cost effective to combine drought-weakened colonies to make California grade, or to overwinter them weak, and let them build to make a honey crop instead. With the price of honey climbing, we can assume that growers will need to offer higher prices to lure those beekeepers to California.

The “Honey Market” card looks like the price may be going up.

Other Sources of Bees

With demand for bees chasing supply, growers are asking, What other options do I have? I will mention some (such as the blue orchard bee, and Canadian bees) later in this article, but for now the Australian package bees are the hot topic (see Bob Harrison’s articles in this year’s ABJ). Importing bees from Australia is a brilliant idea! They are free of Varroa (but not of small hive beetle). When almonds need bees in the middle of the California winter, it is the equivalent of early August in Australia. Australian beekeepers can shake packages and air ship them to San Francisco for about $115 per 4 lb package. We’re looking at 30-40,000 packages coming in this year! We asked the beekeepers and growers we interviewed about their experiences with them. Some had good luck with them, but others were not especially impressed. One Chico beekeeper purchased 4-lb packages in Fall, fed them syrup and three rounds of pollen substitute, yet still had to combine them to make grade. Another beekeeper is offering his grower a deal: “pay for the packages, and I will install them in my boxes in your orchard, and feed them for free, then I get to keep ‘em.”

I do not wish to step on any toes, so I will let hard data speak for me. Dr. Frank Eischen, from the USDA Welasco Bee Lab, tested the performance of Australian package bees in almonds last year, comparing them to overwintered 6- and 8-frame colonies. He did the tedious work of actually counting bees and weighing pollen gathered. To summarize his results, by the end of March, the number of foragers dropped in the Aussie packages, but increased by about 1½ times in the overwintered colonies. The Aussie packages installed in early January were stronger in pollination than those installed in early December. The most telling result was the overwintered 8-frame colonies collected 2½ times as much pollen during bloom than the 4-lb Aussie packages.

It is likely that packages made from August bees dwindle from old age at first, then build up as brood matures (after all, they’re just package bees, not magical). The packages performed well as far as package bees go, and foraged well due to their large brood nests, but were not comparable to good overwintered colonies. So do Aussie packages have value? Absolutely yes! They could be wonderful for shaking onto weak colonies to boost them, and to set a benchmark floor price for colonies as a minimum pollinating unit, i.e., if an Aussie package is worth $125 as a pollinator, then an overwintered 8-framer would be worth 2½ times as much. A knowledgeable source says that the California Almond Board will not be recommending Australian packages to its growers.

The “Other Sources of Bees” card says the Aussie bees will be coming in to make up losses, and set a floor price for colonies. But they won’t fill the demand for the strong colonies growers really want.

Transportation costs and border issues

About 60-70% of the bees going into almonds are trucked in from out of state; therefore, the price of diesel fuel is a large part of the equation if the distance moved is very far. Depending upon who I talked to, it will cost you $15-$30 per colony to haul it roundtrip from the Midwest. Then once you’re in California, you still have cash outflow. A Midwestern beekeeper last year complained that supporting his 3000 colonies in California was costing him and his crew $5000 per week prior to almond bloom for food, lodging, diesel, and bee feed!

Some beekeepers got caught by surprise at the California border by inspections for fire ants and small hive beetle (see Bob Harrisons’s article in March 2006 ABJ). California regulations change from time to time. Don’t go by hearsay—check the source: www.cdfa.ca.gov/phpps/pe/bees.htm. And don’t turn a load back unless you talk personally with the ag commissioner of the destination county!

The small hive beetle remains an issue. Almost none of the beekeepers I spoke to (representing many tens of thousands of California colonies) had ever seen a small hive beetle, although most had heard of someone here who had seen it. It appears to be a problem for some in the southern part of the State, but most California beekeepers are afraid of picking it up in almond pollination from an out-of-stater. Several beekeepers expressed that they would take a lower pollination fee if they would be isolated from out-of-state bees. From a California perspective, we get every new disease and pest from out-of-staters coming into almonds. None of us are enthusiastic about infested colonies being trucked into the state.

The “Transportation” card is that diesel will be up (heard of the Alaska pipeline problems?). Fire ant pressure washings and beetle treatments are costly. Is anyone even thinking about what’s going to happen when diesel hits $10?

Pregame Banter

You now know the game, the stakes, the players, and the hole cards. The game will play out in real life, with some $200 million in stakes. The game will take place between now and February 10th, but I’m going to give you a preview. I couldn’t get the players together for an actual showdown, so I’m going to do the reasonable thing—I’ll make it up. But first let’s start with a pregame discussion of perspectives between two imaginary California beekeepers and two imaginary almond growers sitting in an imaginary California coffee shop discussing the very real opinions I’ve heard (many of them taken verbatim).

Grower George: Growers are upset about the rapid price increase in pollination fees—it doubled in 2006, and now you’re looking to increase it again.

Beekeeper Bob: Hey, you’re not upset about the record prices being paid for almonds! Anyway, we beekeepers didn’t set the price—you growers started a bidding war against each other for a limited supply of bees. Most beekeepers are price “takers” as opposed to price “setters.” In other words, they are just along for the ride on the coattails of what the “big boys” are offering each other.

Grower George: Bees used to be only 8% of my cost of production—now they make up 22%! You’re killing us with high pollination rents!

Beekeeper Ben: Wait a minute, it’s the growers making a killing at our expense! You guys were making a living in 2001 with the average value per bearing acre at $1307; by 2005 it had climbed to $4000! [Almond Almanac].

Beekeeper Bob: Actually, today’s rents aren’t really that high relatively. Look at the following table:

http://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/California/Publications/Fruits_and_Nuts/200605almpd.pdf

#search=%22almond%20yield%20per%20acre%202006%22

*Early August

As you can see, in 1999 through 2001, growers paid an average for pollination of about $53 per $1000 of nuts. The 2006 price was only $59 per thousand (if you sold your nuts for $2.40). But this doesn’t really give the full picture. The “yield per acre” is an average of older, low-yield plantings, and newer high-yield plantings. If a grower is only getting 1000 pounds of nuts per acre, then he should only rent one colony, at a cost of $52 per $1000 nuts at $2.40/lb. If a grower is getting 3000 pounds per acre, then he can rent three colonies per acre at $125, and still only be paying $52 per $1000 nuts at $2.40/lb.! So if you growers only rented as many strong colonies as you needed, your pollination cost as a percentage of nut income would be less than you paid in previous years!

Grower Gerry: I see your point, and I also understand that all our prices are going up. I’m making a good income, and I’m willing to spread it around a bit with the beekeepers. If we don’t help you guys out, there won’t be enough bees to go around in a few years.

Beekeeper Ben: Thanks, Gerry. You gotta realize that we beekeepers see you almond growers buying condos in Tahoe, fancy ski boats, new airplanes, etc. with your almond windfall prices. Meanwhile, bee businesses are going belly up across the country due to disease problems, feed costs, low honey prices. And bad weather. It’s a little hard for us to “feel your pain.”

Beekeeper Bob: This is really a bidding war between the new high-production growers, and the older low-yield growers. It costs a grower about $1000 an acre in operating costs. A new grower getting 3000 lbs per acre at $2.40/lb grosses $7200/acre. Subtract his operating costs, and he nets $6200 per acre. Even a small grower with only 40 prime acres can net a quarter million dollars a year. You won’t find many small beekeepers doing as well!

Grower Gerry: Yep, I’ve got nothing to complain about, so I told my beekeeper that I want three colonies per acre again, and it doesn’t make much difference to me if they cost $100 or $200 per colony, as long as they are strong and give me a good nut set if the weather is bad. I’m not going to be “pennywise and nutpound foolish!”

Beekeeper Ben: I run 2000 colonies, and did O.K. at $80 per colony a few years ago. But last year I was only able to get half my colonies strong enough to take to almonds. My costs are even greater than they were a few years ago, so I can’t get by on half the income. So I gotta double my price to break even.

Beekeeper Bob: I hear you on the greater costs. I never used to fall feed, but now I’m buying yeast by the pallet, and spending twice as much labor keeping ahead of the mites. I’ve got to invest a lot more per colony to get them up to grade. I’ve never worked so hard to keep my numbers up as I have these last two years! Most of my California buddies figure that to stay in business, we’ve got to get something in the $125 to $150 range for strong colonies in almond pollination, long term, and we sure wouldn’t mind a higher windfall bonus if there’s a shortage of bees in the short term.

Grower George: So how much are you pirates going to be asking this year?

Beekeeper Bob: Hey, we never knew what a colony was really worth to an almond grower. We just took your word for how much you could afford to pay. You guys have been whining about prices as long as I can remember. When bees started coming up short, you guys were forced to tip your hand, and show us what bees were really worth to you! I don’t set the price, anyway. I just wait to see what the big boys are getting, and follow them.

Grower Gerry: Last year we heard about the so-called “shortage,” and started off with sky-high prices, then found out that there was a glut of bees, and we got burned. We hear that there are a bunch of starving beekeepers in the Midwest who are going to flood the market this year.

Beekeeper Ben: Flood it with empty boxes? Lots of Midwesterners who came out here for the first time last year lost their shirts. You won’t be seeing them again. Many of the rest are just trying to nurse their starving colonies through the Winter, hoping for a better year next year. Those weak colonies won’t pay the cost of fuel to haul them out here, combine ‘em, and haul ‘em back. The East Coast boys can make more money with a good crop of orange honey in Florida, what with Paramount threatening the orange honey crop in California. This ain’t the same as last year!

Grower George: Last year there were enough bees to go around, and we wound up being able to get bees for $80 just before bloom last year.

Beekeeper Bob: Well, go ahead George, and gamble on waiting until just before bloom. Hope your neighbors have bees, in case you can’t get any! Besides, do you guys really think you’re getting a deal renting 4-frame boxes for $80? Those colonies are so tiny that they don’t fly past the first tree. When you let strong colonies go unrented because you can get discount weak ones, you remove the incentive for beekeepers to produce the strong colonies you really need. If you’re willing to pay 80 bucks for a 4-framer or an Aussie package, you should be even more willing to pay $200 bucks to the guy who is offering 16-frame “boomers!” Those are the bees that will set you a crop in any weather.

Beekeeper Bob: I agree! If you guys want to be knuckleheads and pass up strong colonies for $80 four-framers, then I’d make more money by doing some colony strength “hocus pocus.” I could split my 16-framers into four 4-framers and add Hawaiian queens, thereby clearing an extra $150 for the same bees by spreading them out into more boxes. In fact, by lowballing, you give unscrupulous beekeepers an incentive to rent you queenless splits that would pass for 4-framers, but would be worthless for pollination since they would have no brood. You’re going to get what you pay for, and that may not be what you want!

Beekeeper Ben: What I’m saying, is that if you guys want strong, healthy colonies that will reliably set a good crop for you, you’ve got to make it worthwhile to the beekeepers.

Grower George: I hear the boys coming in the door. It’s time to start the game, and see what a strong colony’s gonna be worth!

The Game

Here’s the poker table—a motley crew of large and small beekeepers from all over the U.S. (reeking of

Bee Go and smoke), an Australian observer (just drooling at all that California money), California almond growers from North and South Valley, both large and small (some flying in by private plane, some in battered pickups), a smattering of brokers, and various assorted speculators, gamblers, and crooks hoping to get in on a cut of the action. Everyone’s munching on smoked almonds and beer, and the atmosphere is guardedly festive. [Author’s note: the players described are imaginary, but the comments, and figures quoted mid August are very real.]

Paramount Farms antes up in the range of $125 (but covers his butt by reserving the right to adjust).

The Dealer deals the cards. Everyone stares at the hole cards lying face down.

Everyone knows that “Demand” will be going up to some extent—2% to 6%.

California beekeepers feel pretty good about the “Mite” card this year, we’re not sure about the Midwest, so it could turn into a wild card come January when the bees try to build up.

The “Weather” card is wild—leaning toward a Midwestern disaster, no telling about Winter or Spring.

The “Honey Market” looks to be headed up, due to such arcane events as a typhoon halfway around the world, so it will be competing with almonds for bees.

The Australian observer keeps his eye on the “Other Sources of Bees” card. If the U.S. supply goes south, he stands to make a killing.

The “Transportation” card took a hit with the Alaska pipeline disaster.

Joe Traynor speaks first: “I’m holding at $159 (with quantity discounts) to the Grower, for 8-framers.”

The Small Beekeeper passes: “Remember, I’m just along for the ride.”

The Large Grower, looking nervous, offers $150 to anyone who will take it. Some do.

One Big Broker, hiding his cards, says “I’m looking at the Midwestern disaster, and I’m gonna hold tight for a while. I think you guys are dreamin’ that there will be enough bees—I think we’re gonna hit $180 or more!” (Some beekeepers grin and elbow each other with anticipation)

The Gambling Beekeeper: “Me, too. I’m holding my bees ‘til the last minute, and hope to make a killing by charging some desperate grower $200 per colony!” (Eyes roll in the crowd)

The Gambling Grower: “You’re crazy. I hear those desperate Midwesterners are going to flood the market with cheap, weak colonies. I’m gonna wait ‘til the last minute and get leftover bees for $80 again.” (He frowns when he hears snickers from the beekeepers.)

The New Age Almond Grower: “Can’t we all just work together and cut back to a colony or two per acre like Joe says, so there will be plenty of bees to go around?” (The rest of the growers suddenly find something to look at on the floor)

The California Broker: “I just ask beekeepers what they want. Those calling me at this early date are asking in the 125-140 range for decent bees. But most are asking me what I think the market will do.”

The Big California Beekeeper: “I’ve got a few really good yards that I’m setting in with Joe. My weakest yards I’m offering to those so-and-so’s at Paramount, and the rest I’m shopping out in the $135-$160 range, depending on how the orchards look, and how far I am from those beetle-toting out-of-staters.”

A South Valley Grower: “I’m not as tough on inspection as Joe is, so I’m offering my beekeeper a good deal at $145.”

Another South Valley Grower says: “I’m don’t expect much rain in Winter, so I’m gonna just take two colonies per acre, but I’ll pay for premium bees, and go $160.”

The Cautious Grower: “You may want to gamble on cutting your bees tight, but not me. I figure, if almonds are selling at $2 a pound, I can recover the cost of an extra colony per acre at $140 with only a 3.5% increase in my ton/acre nut production. That’s a no brainer—I’m going for the extra colony.”

The North Valley Grower says: “You guys are killing me. I can’t count on good weather, I’m going for three colonies, but I’ve got some local guys that will bring ‘em in for $150, with a clause to adjust for market. I gave ‘em $10 extra two years ago, and last year, they gave me $10 back when prices tanked.”

A Really Big Midwesterner drawls: “I’m kinda like you. I’m signing now at $140, but my growers promise to go up or down $10 depending on how the market plays.”

Another North Valley Beekeeper: “I’m surrounded by bee guys that don’t have to drive far. They’re talking in the 135-160 range.”

The 1000-colony California Beekeeper: “I’ve been going with the same grower for 20 years—we’re like family. I bring him good enough bees, no strength guarantee, every year. He gravels the roads, and pays me in advance. For that kind of consideration, I’ve signed for $125.

The Florida Beekeeper: (Looking at the Honey Market and Transportation hole cards) Do you know how hard and expensive it is to travel clear across the country? Paramount’s making Florida orange honey look mighty sweet. You California boys are gonna have a hard time getting me out there again.”

The Texas Fire Ant Cowboy: “I had to get my truck pressure washed at the border last year, and that shot my profit. I went in for $150 last year, but won’t do it that cheap again.”

The 50-Colony Californian: “My grower’s wife brings me out iced tea, and I give her a case of honey, but their orchard is a pain in the butt getting in and out of, and they want 6-colony drops. But they’re willing to pay $160.”

The Midsized Grower: “My bee guy said an Act of God killed his bees, but I think it was the witches brew he was counting on for varroa control. He’s buying Aussie packages to restock, and I’m promising him $125 if they look O.K. by bloom.”

The Disgruntled Midwesterner: “A bunch of us got “burned” in California last year, with your ‘California Grading.’ Our bees aren’t looking great this year, so we’re probably going south for honey. It will take a damned pretty penny to lure us out again, and you’ll have to pay us in advance.”

The Still Beeless Grower: “Just how much is a ‘pretty penny?”

The Disgruntled Midwesterner: (Trying to sound ominous) “I guess we’ll see in January.”