The Rules Redux

My recent article, “The Rules for Successful Beekeeping,” got more response (overwhelmingly favorable) than all my previous articles combined! (I’ve received requests to reprint it in several foreign countries, including a translation into Serbian!). What I also discovered is that there are a few beekeepers suffering from advanced cases of HDD—Humor Deficit Disorder. This is cause for concern, as a good sense of humor is critical for successful and enjoyable beekeeping!

The Rules Redux

Randy Oliver

ScientificBeekeeping.com

First published in ABJ October 2011

Reason and Common Sense

Two things inspired me to write that article:

- The dismay and confusion that I hear from newbies about making sense of rigid and conflicting rules as to how they “should” keep their bees, and

- The pleas that I’ve heard from beekeeper after beekeeper about their local club being hijacked by some cadre of well-meaning, but fervent “true believers” in some particular set of rules.

I’m seeing a problem—there’s currently a huge resurgence of hobby beekeeping, yet our bee researchers and extension apiculturists are so afraid of offending someone, that they don’t dare publicly speak their minds about some of the fads and cockamamie ideas being promulgated to naïve beginners. So I took it upon myself to do the offending! (Yes, the sentence above was intentionally offensive, just to make sure that I get this article off to a good start. That’s my kind of humor.)

In my articles, I’m generally not much one for judging or criticizing others, but I wanted to make the point that there is no one “right” way to keep bees. I decided to follow the style of the American revolutionary Thomas Paine, who, in his essays “The Age of Reason” and “Common Sense,” humorously and irreverently pointed out the fallacies and inconsistencies of the reigning institutionalized religious dogma.

I was looking for a way to get the attention of folk who just go a little bit overboard with their zeal to impose their belief system upon other beekeepers. I had heard the term “Beekeeper Taliban” from a correspondent in the U.K., and felt that it was perfect for humorously describing some of the more fervent proselytes.

What I had hoped to accomplish with the Taliban analogy was that it would get some of the more adamant rule makers to look at themselves in the mirror, and perhaps see that there was more than one path to Beekeeper Enlightenment. I had hoped that by rationally discussing some common misconceptions, that they might rethink their dogma. And maybe I did get into their faces a bit, but that’s my nature—I’m not forcing anyone to read my articles!

To my surprise, I found that certain beekeepers suffer from serious HDD, and missed the entire points of my article, which were “lighten up, allow others to keep bees any way they wish, and that the only ‘rules’ that the bees follow are those set by Mother Nature.”

Unfortunately, some folk were so offended that I received a few excoriating emails and phone calls. My intent was not to incite divisiveness or defensiveness (as I feel that most all beekeepers have essentially the same end goals) but rather to provoke some of the more rigid practitioners into introspection.

Ross Conrad begins the preface to his excellent and popular book Natural Beekeeping with an appropriate quote from Francis Bacon:

Read not to contradict nor to believe, but to weigh and consider.

I am in total agreement! I’m not trying to convert anyone to anything, nor to be disrespectful to any school of thought. But it’s clear that at least some readers misunderstood what I was trying to accomplish! With that in mind, I’d like to address some of the comments by my critics, as the last thing that I want to do is to polarize the beekeeping community.

Critic: “When you call a group a Taliban it does give it a harsh feeling. I think it is wrong to compare a group of beekeepers to a group of suicide bombers. It doesn’t matter if they are saying there is only one way of beekeeping.”

The Taliban analogy was simply about rigidity and righteousness, and imposing one’s beliefs upon others. And I feel that it does matter if they don’t let beginning beekeepers know that there are other viable and ecologically-sound options. (The above critic actually cancelled a speaking engagement of mine after reading the article—that is Taliban-like behavior (the decision was later rescinded)).

Critic: “If someone doesn’t agree with your rules, then you call them the Taliban!”

As for “my” rules—that bees need good food and a warm, dry cavity, and suffer when exposed to parasites and toxins—these rules are set by Mother Nature, not by Randy Oliver! My Taliban analogy wasn’t about any particular set of rules, but rather about anyone forcing their own belief system down the throats of others.

The Rules of Nature

Paul Newman, in the role of Butch Cassidy, gave a succinct and eloquent demonstration of the rules of knife fighting in a scene of that namesake movie (there ain’t any rules). The same applies to Nature. As a biologist, I do not have the romantic perception of a benevolent and harmonious Nature that some embrace—Nature is an ever-evolving tooth-and-nail fight without rules, in which only the most fit survive, and in which the “normal” yearly death rate of “wild” colonies of bees exceeds a commercial beekeeper’s worst nightmares!

In Nature, whatever works, wins the fight (and it is a constant fight for resources, in a contest against members of your own species, other competitors, predators and parasites). In the case of the honey bee, the species is in serious competition with humans for suitable forage, as we convert productive land to pavement, housing, lawns, and pesticide-laden monocultural cropland unsuitable for bee survival. In addition, we have imported a slew of new parasites that have added serious challenges to bee health overall. I myself feel that we owe it to the bee to help it deal with problems that we ourselves have created.

The better that one understands the reality of the rules of Nature, the better one can then adjust their management practices to be successful at beekeeping in their particular situation and environment. When I teach beekeeping classes, I begin by telling my students that I am not going to give them any rules whatsoever; instead, I explain bee biology and behavior so that they can make appropriate management decisions of their own. If one bases their methods upon the natural rules that bees invariably follow, then even in these days, beekeeping can be successful and profitable.

The Facts

Critic: “I just read your “Rules for Scientific [sic] Beekeeping” piece and if you genuinely believe that pile of nonsense, then you really should drop “scientific” from your domain.”

As always, I implore my readers to point out any factual errors in any of my articles, as I am eager to correct them! I’ve got no position to support, and only wish to share accurate information to all beekeepers, no matter their particular philosophy.

He continues: “This sort of rhetoric not [only] undermines your entire argument, but paints you as a reactionary lashing out at what you fear.”

Actually, what I fear are people who allow their emotions to overcome their reason!

Folks, I claim the right to speak frankly and openly since I’ve run the gamut from being an extreme green “alternative” hobby beekeeper to a professional migratory pollinator, queen breeder, and honey producer. I pride myself upon keeping an open mind, and being able to look at things objectively. I assess these issues through the eyes of a scientist, tempered by my experience in the school of hard knocks.

Pragmatism

I write for an audience that has a specific outcome in mind—keeping healthy, productive colonies of bees in a profitable manner. Thus, all of my management suggestions are outcome based—meaning that they’ve been tested and demonstrated to make a measurable improvement in colony health or production. I do not write to support any particular philosophy or “faith.” I don’t tweak my facts to suit my opinions or prejudices; rather, I try to understand why some beekeeping practices work, and why others don’t.

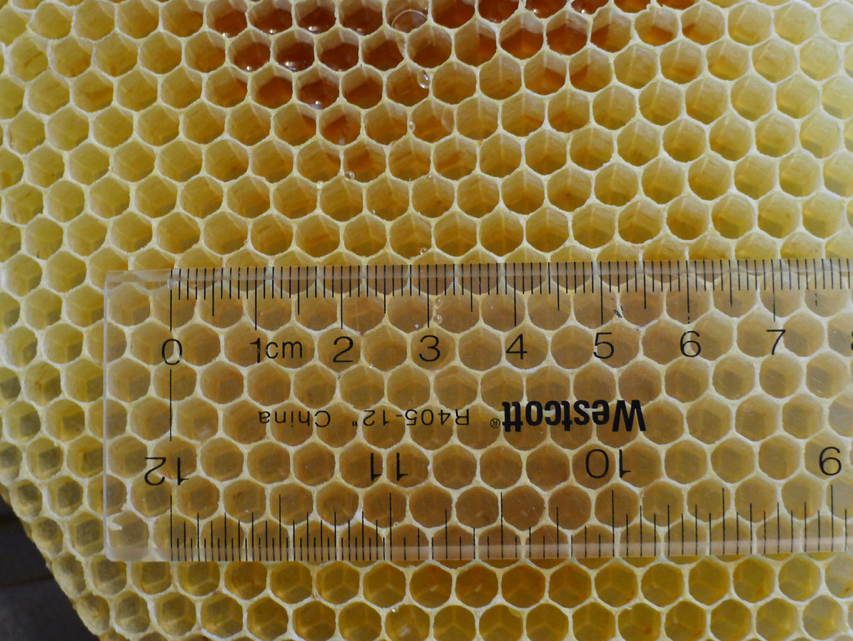

Small cell foundation sure sounds like an easy and natural way to control varroa mites; regrettably, several scientific studies (reviewed in Seeley 2010) found that it had no effect! Despite its apparent lack of efficacy, some still cling to it as an article of “faith” (oh, that statement’s gonna tick some folk off!). Until I see a single controlled trial in which colony survival is better in the small cell group, I must remain skeptical. I grabbed a naturally-built comb out of one of my hives for this photo–note that the cell spacing is the same 5.4mm as in standard foundation.

I generally go out of my way in my articles to be non judgmental, and to keep my opinions to myself. The old saw goes that if you ask ten beekeepers how to do something, that you’ll get at least a dozen different answers. But simply believing that something’s gotta work doesn’t necessarily make it true in real life—I’ve heard many management suggestions that make complete sense when you first hear them, but upon deeper analysis run contrary to natural bee behavior, and often work against the bees! To me, the bottom line is, is the advocated method consistently successful? Does it result in healthy colonies that produce a harvestable honey crop, and then survive until the next season

One thing that bothers me is the vast amount of questionable beekeeping recommendations on the Web, and the fuzzy thinking behind some of the management advice being promoted to “save the bees.” Much of this advice is based upon wonderful idealism, or a fairy-tale version of Nature, or the anthropomorphizing of bee behavior. I, on the other hand, am a hard data kind of guy.

The Soul of the Hive

Hey, I love the magic and mystery of bees and beekeeping, and never lose the thrill that I get when I open a hive and peer into the heart of the superorganism that we call the honey bee colony. I doubt that there is an experienced beekeeper alive who isn’t enchanted by the vibe of an apiary working a spring flow, or who doesn’t recognize the vibrant soul of a growing colony with a fresh young queen!

That’s all the poetry you’re going to get! I suggest that the reader question any management recommendation based upon how bees must feel, or must think. Let me tell you, it is a huge mistake to anthropomorphize bees! Bees are not humans, and live in a totally different reality. I suggest that you read my articles The Economy of the Hive and The Primer Pheromones, to better understand the actual rules that govern bee behavior.

The bee books often refer to colony “morale.” This is about as close as you are going to get as far as hearing a scientist or commercial beekeeper talk about the soul of the hive, but I suggest that the two terms are synonymous—the best beekeepers are those who have that special “feel” for colony morale, and work to maintain it.

And again, most of colony morale goes back to Nature’s four rules: nutrition, cavity, parasites, and toxins. And add to that the condition of the queen—communicated to the colony by her pheromone output (see James Bach’s recent articles in this Journal). So I question rules that prohibit requeening, and suspect that they were written at a desk, not by someone actually immersed in an apiary.

It is a lovely romantic notion that a colony will “mourn” the loss of their dear queen mother. But the reality is that they will supersede her in a heartbeat should she begin to fail, and that introducing a vibrant young queen generally gives a colony a new lease on life. So I just can’t see why some “natural” beekeeping rules prohibit beekeepers from raising daughters from their best queens, so that their offspring will be suitable for local conditions and can deal with local parasites and pests.

The “soul” of this hive is filled with love—you can see it in the way that the nurses form a tight retinue around this queen. But they don’t care whether the queen is their natural mother or not!

My point here is that arbitrary rules about how one should keep bees often more reflect the prejudices of the beekeeper, rather than the actual biological responses of the bees.

“Saving the Bees”

When CCD hit the press, and thus the public’s attention, folk came out of the woodwork with ideas that they were sure would “cure” CCD (I got dozens of emails and phone calls from them). Although these people are earnest and well-meaning, most of them have not made the effort to really understand just how their method applies to the reality of bee biology.

In truth, there is little evidence that the bees actually need “saving”—worldwide, the number of managed colonies is increasing, there have recently been enough live hives for almond pollination, and feral populations are rebounding in a number of areas. Many of us, even those using “standard” beekeeping practices that focus upon good animal husbandry, maintain thriving apiaries (ironically often selling replacement bees each year to those very beekeepers who are on a quest to teach us how to better keep bees!).

Critic: “The fate of bees does not rely on man; the fate of man relies on honeybees.”

Very poetic, but hardly true! The Native Americans had thriving agricultural societies in the absence of Apis mellifera—mankind could well exist without honey bees. Conversely, the fate of the honey bee in certain areas has much to do with man, as it is through our actions of habitat destruction, monocropping, environmental pollution, overstocking, and pathogen transportation that many of today’s bee problems arise.

On the other hand, I don’t understand what makes people think that proven management practices that for decades resulted in healthy, productive hives were suddenly responsible for CCD! Langstroth was a keen observer of the nature of bees, and his hive design has been so successful because it is based upon natural principles of bee behavior. Similarly, bees thrived (and still thrive) on comb foundation. I’m not saying that either couldn’t be improved, but there are tradeoffs—e.g., deeper combs result in heavier boxes, and naturally-drawn combs are not interchangeable throughout the hive, as the bees tend to build different cell sizes in different areas of the cavity and dependent upon the immediate needs of the colony.

Similarly, there are races of bees that naturally migrate to better pasture, so blaming CCD on migratory practices per se is plain silly. Same with the feeding of sugar syrup—bees thrive on sugar syrup, since their main source of nutrition is pollen (I’m not so sure about various high fructose corn syrups). I avoided feeding bees sugar syrup or pollen sub for twenty years, instead moving them seasonally to better pasture. That worked great! But then I got tired of the trucking, and found that sugar syrup is like a magic wand in beekeeping, and can be used judiciously with incredible results. Ditto with pollen substitute, especially in our dry California summers. Reality trumped philosophy!

Natural Beekeeping

Critic: “It sounds like you’re down on natural beekeepers.”

Nothing could be further from the truth! Please allow me to emphatically state that I support “natural beekeeping.” What I have a problem with is when it becomes a religion. I’ve got the same problem with organic gardeners—despite the fact that I’m an organic gardener myself, and that I keep apiaries on organic farms, I’d like to suggest that perhaps some proponents could serve it up with a little less self righteousness. As a good example, I think that Ross Conrad did a nice job of presenting natural beekeeping without being too heavy handed. I also peruse other natural beekeeping websites for ideas, although all suffer from a lack of hard data to support their conclusions.

This is the main problem with making sense of “natural” beekeeping methods—it’s hard to tell which are snake oil and which are truly effective, unless someone has actually compared a dozen test hives against a dozen controls in the same yard, holding all other variables the same. Without such simple trials, proponents of any particular method are just talking out of their hats.

However, my feeling is that “natural” and “organic” beekeepers are on the forefront of developing apiary management techniques that are sustainable and ecologically friendly. In that, I fully support their efforts, because should they come up with economically successful best management practices, I predict that they will continue to be adopted by the bee industry as a whole.

The method that takes the prize for being “most natural” is probably the Warre hive, although I doubt that many will want to deal with the lifting and hassle involved in extracting honey. However, I’ve yet to see any sort of demonstration that bees are any healthier or productive under such management.

Critic: ‘The reality of the situation is that if your “rules” are truly the only way to do things, then Kirk Webster wouldn’t be doing what he’s doing in Vermont. Sam Comfort would be out of business and our hives wouldn’t have such a low mite throughout the year that we have a hard time finding the little beasts.”

I have to question whether the critic actually read my article, as the only “rules” that I offered were those given by Nature. I didn’t give any rules whatsoever as being the “only way to do things”! Even odder is the writer’s reference to Kirk and Sam, each of whom I consider as friends and exemplary beekeepers. Indeed, Sam makes the point that he himself doesn’t make any rules for other beekeepers (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aOuPA-BUmcE&feature=related).

Speaking of Kirk and Sam, to their credit they not only talk the talk, but also walk the walk (in different ways). They each have experience with various sorts of equipment and management, and successfully (meaning that they consistently have surplus bees to sell—not sure about their honey production) run their operations without benefit of mite treatments. I applaud their success at being “natural” beekeepers.

“Alternative” Doesn’t Necessarily Mean “Better”

Especially if one simply switches from one rigid orthodoxy to an equally dogmatic alternative! The reality is that virtually every serious beekeeper experiments with “alternative” methods. One would actually be hard pressed to come up with any truly new “alternative” idea in beekeeping!

I suggest that the curious beekeeper read the old masters from the mid 1800’s on. These guys really knew their bees, and were hard-core innovators! I highly recommend the book The Hive and the Honey Bee Revisited, in which Dr. Roger Hoopingarner annotates Langstroth’s original 1853 publication with up-to-date footnotes of current apicultural science. As Dr. Roger Morse was fond of saying, “there is nothing new under the sun in beekeeping.” It’s funny how beekeepers continually think that they are inventing something new, whereas in reality the old boys have often already been there, and done that!

Varroa management, of course, is the exception. Beekeepers have been forced to learn new practices for keeping their colonies alive and healthy. Necessity being the mother of invention, a plethora of new methods were spawned, most of which, no matter how much sense they seemed to make at the time, or how good they made the beekeeper feel, unfortunately proved to be ineffective.

A number of the management techniques that I’ve written about over the past few years were at the time considered to be quite “alternative.” Some I’ve incorporated into my own operation, and several I’ve abandoned for various reasons. At this point in time, progressive beekeepers (meaning those that are willing to learn and change) are staying on top of most problems, and doing quite well at beekeeping. So they are understandably of the mindset that, “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it!”

I’m all for trying new ideas, but then test them in a controlled trial to see if they really work! What bothers me is the promotion of “alternative” methods long after they’ve been discredited. I heard of lot of this during my recent visit to New Zealand, where beekeepers eager to control varroa by alternative methods were trying stuff that they got off the internet, not realizing that the methods had already been tested over here and found to be ineffective!

Arbitrary Rules

The problem that I have with some “natural” beekeeping advocates is that they have created new rigidities and “rules,” such as which sizes or shapes of boxes or frames are “allowable,” forbidding the use of queen excluders, specifying exactly how far apart or inches above the ground that hives must be kept, that the only acceptable means of propagation is through natural swarming, etc., etc.

For example, one set of standards specifies that: “supplementary winter feed must contain at least 10% honey by weight. This must come from a … certified source. Camomile [sic] tea and salt should also be added to the feed.” Oh my God, teatime with salt for the bees?

To me, those are completely arbitrary “rules.” And oddly, various “natural” beekeepers completely disagree upon those rules. Some “natural” beekeeping gurus feed sugar syrup, many raise queens and split hives, some move their hives to better forage, and many control parasites with “natural” chemicals. I don’t see any problem with any of the above details. To me, if your bees thrive and are productive year after year, then you are obviously doing things right and in a sustainable manner.

As far as niggling rules about details, note that some of the largest honey crops in the world are produced through queen excluders, so it’s hard to explain how excluders are harmful to the bees. To me, an excluder is no more “unnatural” than using a fence to keep the cow out of the garden.

Treatments

Critic: “Randy chooses to embrace chemical treatments of his bees. That’s his prerogative. He very fervently justifies this to himself and to others through his talks and writings. If you don’t agree he brands you a Taliban. I’m suspicious of this zeal to righteousness.”

This one came out of left field! Especially since I don’t give a squat whether anyone agrees with me or not! Oddly, in the referred talk, I had clearly stated that selective breeding was the solution to parasite problems, I detailed biotechnical methods of mite management, I showed tables of the comb contamination due to miticides, and I suggested using “natural” treatments only if mite levels got too high! I guess that one is only going to hear what one wants to hear!

I’ve been a major proponent of selective breeding for treatment-free bees ever since varroa arrived (I had previously had great success at breeding bees for resistance to AFB and tracheal mite). My goal has always been to keep bees without the use of any treatments. In that pursuit, I’ve allowed more colonies to die than the above writer will likely ever see. But what I found is that if I wanted to make a living as a beekeeper, then I needed to use some treatments to keep my hives alive!

I personally haven’t used synthetic miticides since the turn of the millennium–for practical reasons. The synthetics offered to date are not sustainable (as the mites eventually develop resistance), residues of some build up in the combs and negatively affect bee health, and I’m concerned about the public perception of the purity of honey being tainted by such chemicals.

Luckily for beekeepers today, there are four effective, totally “natural” and noncontaminating mite treatments available in this country—thymol, formic acid, hops beta acids, and oxalic acid (technically not yet registered). The use of these botanical or organic acid treatments is, in my opinion, little different than using herbal extracts or apple cider vinegar to treat yourself for parasites. I honestly don’t see how evaluating their efficacy means that I’m “embracing chemical treatments”!

Some Rules are Not Arbitrary!

When it comes to treatments, including those derived from natural sources, you must use common sense! Thymol, hops acids, and oxalic acid could all be considered to be “botanicals” which are normal parts of our diets (hops if you drink beer). However, in the concentrated form, they must be handled with caution, just as you would afford to habanero peppers. Especially keep them out of your eyes! Follow the label rules!

I’ve had extensive experience with Apiguard thymol gel and oxalic acid dribble, and can attest that they are not only reliably effective miticides, but also extremely safe to handle, and no big deal if you get some on your skin (other than your face) and simply wash it off. I have less experience with Hopguard, but can tell you that it doesn’t cause me any skin irritation. However, it is prudent, even with these natural miticides, to always wear mechanic’s nitrile gloves, and to keep wash water at hand.

Formic acid is another matter—it’s the burning component of stinging nettles and ant defense. You need to wear protective gloves! However, my common sense finds that the respirator rule is ridiculous. Amazingly, bees, perhaps due to their long association with ants, appear to tolerate formic fumes easily.

To put things into perspective, yesterday I safely applied 48 formic strips, then damn near asphyxiated myself when I stopped for a snack and accidentally squirted a little malt vinegar down my windpipe—in case you’re curious, THAT will clamp your trachea shut in a heartbeat and prevent you from breathing! (Don’t ask). My point–vinegar is an organic acid that is considered to be so safe that it comes without any safety warnings, yet it nearly killed me! You must use common sense when handling any strong organics.

I tested MAQS formic gel strips in fall and spring, and they were very easy to handle. However, those that I’ve tried since the weather turned hot are gooey, sticky, and harder to unwrap and handle. WARNING: the sticky gel causes only a slight tingling on exposed finger skin—but will later cause blistering! (Don’t ask).

Treatment-Free

Critic: “What have you got against treatment-free beekeeping?”

My guess is that the majority of nucs that I sell each year (several hundred) never see a treatment. The feedback that I receive is that they survive just fine, and produce honey year after year. I’m all for keeping bees without treatments so long as they stay healthy.

The problem that I have with those who go treatment free is that if they allow colonies to die and get robbed out, they spread a load of mites and viruses to their innocent neighbors. To me this is irresponsible beekeeping, and a waste of valuable colonies. I don’t see any reason to subject a strong colony of bees to an awful death due to the defective genetics of their mother. Just treat ‘em and requeen ‘em!

Critic: “What evidence do you have that allowing colonies to die from mites causes mite drift to your neighbors’ hives.”

Plenty of beekeepers (including myself) have learned this the hard way. Smart commercial beekeepers keep a close eye on their neighbor’s mite loads, and will actually move away from apiaries with problems. If you want numbers, a recent study from Germany (Frey 2011) documented the immigration of mites from collapsing hives into other hives a mile away.

Some folk make the mistake of thinking that the only way to breed mite-resistant bees is by setting up a “Bond Yard” (live and let die). Doing so will definitely weed out all susceptible stocks, but the end result (if any survive) is generally a feisty, swarmy bee that maintains a small colony, restricts drone production, and doesn’t produce much honey (Locke 2011). However, once you’ve locked in resistance, you can then start breeding for more manageable bees. This approach has been followed independently with excellent results by John Kefuss, the Baton Rouge Bee Lab, and numerous independent breeders.

However, there is an alternative approach that works from the opposite direction—start with gentle, productive colonies, bring in some resistant stock as drone mothers, and then propagate each year only from those productive colonies with the lowest mite levels. No colonies need to die, since you simply treat and requeen any that start to get overwhelmed by mites. This approach may take a bit longer to reach full resistance, but the upside is that you stay in business during the interim. I’ve had considerable success with this method!

Commercial Beekeeping

I don’t see any reason to demonize commercial beekeepers—they have enough troubles of their own. Yet I’m constantly seeing them being painted as bad guys (just listen to the soundtrack of the popular movie “Queen of the Sun”—the music shifts to ominous each time that a commercial bee operation comes on screen).

Most commercial beekeepers dream of going back to managing only a few hives in the backyard—but are forced to adopt an agribusiness model in order to supply the demand for bees by American farms and orchards. These hives belong to one of the best and most conscientious beekeepers I’ve met.

It’s clear that some of the industry’s problems are self-inflicted—e.g., too much reliance on antibiotics, inadvertent miticide contamination of comb, and the overstocking of yards. But these sorts of problems are associated with all industrial-scale animal husbandry. Not to mention that for a time, there were no safe and effective legally-registered miticides, forcing them to…let’s not go there! I’m not defending all commercial practices, but can say that the big boys are by and large very smart guys, and are adopting more sustainable varroa management practices.

What bothers me is the current schism between recreational and commercial beekeepers. The smug attitude by some hobbyists that they know so much more than professional beekeepers (who spend their every waking hour immersed in caring for their bees) is counterproductive. The collective knowledge of large-scale beekeepers is a vast resource that the recreational beekeepers can benefit from, and should pay attention to! Might I suggest that one not judge another until you’ve walked in their shoes—you don’t need to criticize others in order to become a good beekeeper yourself!

Bee Husbandry

The only beekeeping rules that I promote are those of common animal husbandry—give your bees a clean, warm nest, nutritious food, suppress parasites if necessary, and avoid toxins. As a beekeeper, I enter into a contract with “my” bees—I provide good husbandry, and they repay me in kind with honey, pollination income, and offspring for sale. It’s as simple as that folks—don’t let anyone tell you that there are any other “rules” that you need to follow. Oh, and keep a sense of humor!

Allow me to end this discussion with a quote from Ticknor Edwards (1920):

“The bees have their definite plan for life, perfected through countless ages, and nothing you can do will ever turn them from it. You can delay their work, or you can even thwart it altogether, but no one has ever succeeded in changing a single principle in bee-life. And so the best bee-master is always the one who most exactly obeys the orders from the hive.”

A Request from the Author

For those of you now all fired up to send me an incendiary reaming, please put “Hate Mail” on the subject line in order to save me time. I’m not criticizing anyone personally, and know that you all have the best interests of bees and the Earth in mind. On the other hand, I welcome rational discourse about any factual errors in my articles, and solicit reports of any testing of alternative methods that you’ve done, so long as you ran a control group for comparison.

References

Frey, E, H Schnell, and P Rosenkranz (2011) Invasion of Varroa destructor mites into mite-free honey bee colonies under the controlled conditions of a military training area. Journal of Apicultural Research 50(2):138-144.

Locke, B I Fries (2011) Characteristics of honey bee colonies (Apis mellifera) in Sweden surviving Varroa destructor infestation. Apidologie 42: 533–542.

Seeley, TD and SR Griffin (2010) Small-cell comb does not control Varroa mites in colonies of honeybees of European origin. Apidologie 42(4): 526-532.

Tags: commercial beekeeping, husbandry, redux, rules, treatment